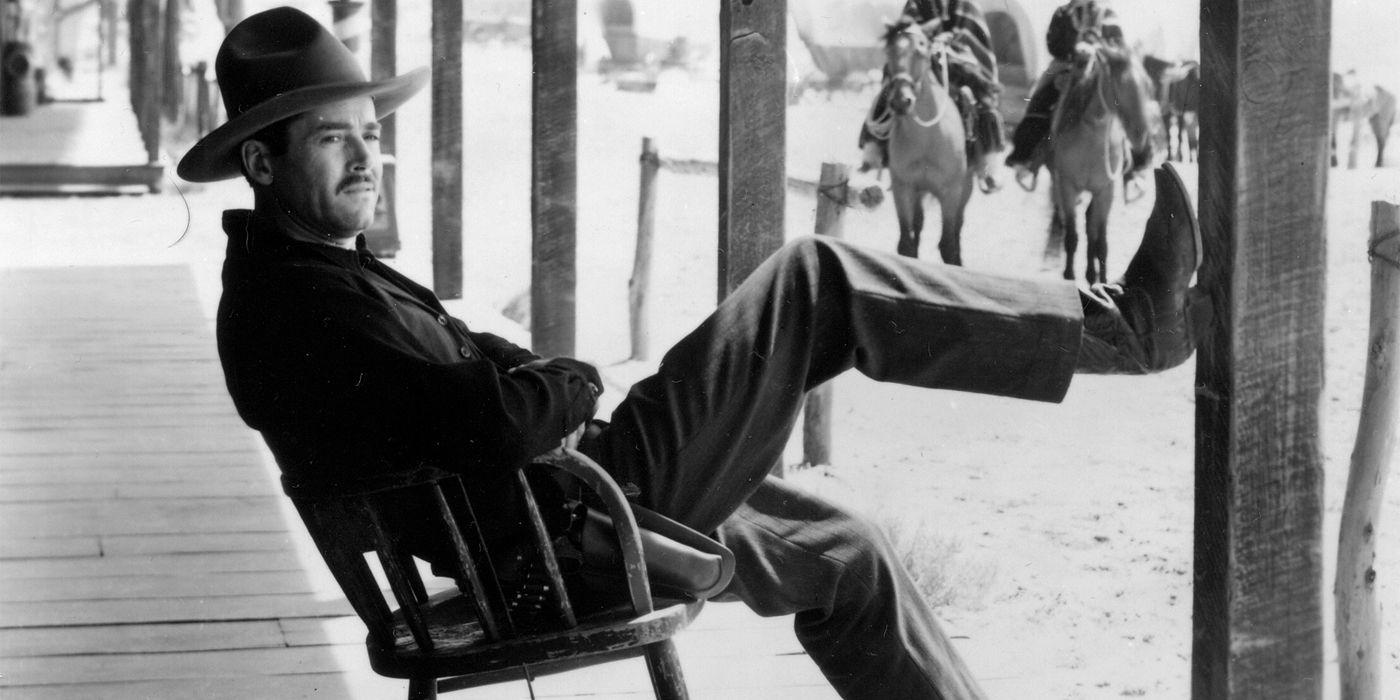

For legendary filmmaker John Ford, telling the story of the American West through a demystified lens is conveyed through a singular image. In 1946, a shot of Henry Fonda sitting on the porch of a local barbershop, leaning back on a chair as he looks upon the open vista is a minimalist example of Ford’s painterly visual language. This shot defines Ford’s remarkable film, My Darling Clementine, and the thesis of one of the genre’s darkest turns. No genre actively engages in revisionism quite like the Western. Ford is certainly no stranger to acts of legend reconsideration. When applied to historical events, genre deconstructionism manifests with even greater pathos.

- The Most Ethically Gray Anti-Hero in a Film Is a Studio Exec, Obviously

- ‘The Wizard of Oz’ Was Not the First Color Movie — This Was

- The Only Movie Marlon Brando Directed Was a Stanley Kubrick Western First

- ‘The Nun’ Recap: Everything To Remember Before Valak Haunts Again in the Sequel

- ‘A Man Called Otto’ & ‘A Man Called Ove’: A Tale of Two Adaptations

Is ‘My Darling Clementine’ a True Story?

My Darling Clementine chronicles a loose account of Wyatt Earp (Fonda), who, after the slaying of his younger brother by a band of outlaws outside of Tombstone, Arizona, accepts the job as the town’s marshal to enact revenge along with his two other brothers, Virgil and Morgan. He strikes a reluctant partnership with the feared local gambler, Doc Holliday (Victor Mature), and becomes enchanted by the lavish spirit of two women, Chihuahua (Linda Darnell) and Clementine (Cathy Downs), with the latter being Doc’s former lover. The film builds towards the fabled gunfight at the O.K. Corral between Earp and the Clanton Brothers, the cowboys responsible for killing James Earp and ravaging the family cattle.

Western historian Andrew C. Isenberg details Earp’s fixation on his public image in media in a featurette included in My Darling Clementine‘s release on the Criterion Collection. Toward the end of his life, he moved to Hollywood to influence his credibility as a noble enforcer of the law on the big screen. As a result, with the foundation of a favorable biography of the man in 1931 by author, Stuart N. Lake, the cinematic depiction of Earp and his role in Tombstone was glamorized, as seen in early films such as Wild Bill Hickok in 1923 and Frontier Marshal in 1934, which is directly based upon Lake’s book. During his stay in Hollywood, Earp befriended William S. Hart, a famous onscreen cowboy at the time, and served as a consultant to several silent Westerns. Fittingly enough, Earp, who passed in 1929, would even visit the sets of John Ford films.

On the surface, My Darling Clementine is guilty of the same misdemeanors of altering history onscreen. Isenberg states that the specificities of the Earp family’s background, Wyatt’s fortitude as a sheriff, the antagonism of the Clanton family, and the results of various events are adjusted, if not completely false. The Earps were hardly farmers or cowboys, but rather steadfast gamblers. The film presents Wyatt as the head of the family, but history shows that Virgil was the true leader — one that Wyatt admired. In the grand outlook of his life, Wyatt’s period as a law official is marginal. The vilified Clanton family in the film was hardly a posse of ruthless crime bosses. In actuality, they were working-class folks in the same mold as the Earps, which counters the public sentiment that the duel at the O.K. Corral was a bout between good and evil.

The Deeper Meaning Behind ‘My Darling Clementine’

When all the factual errors are disclosed, it only serves to crystalize the poetic beauty of John Ford’s film. The director’s manipulation of historical accuracy simplifies the narrative so that it can focus on the most thematically rich elements commonly found in Ford’s best films, including How Green Was My Valley, The Searchers, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. Film critic David Jenkins, in his supplemental essay for the Criterion Collection, writes that Clementine “shuns any sense of down-home triumphalism and goes out of its way to suppress anything that might be deemed a glamorization of cowpoke lore.” In other words, Ford’s recognizable revisionism is channeled through the perspective of tainted souls, rather than active reexamination of Western folklore’s skewed relationship to the founding of America and the treatment of Indigenous people.

My Darling Clementine was released one year after the conclusion of World War II. The aimlessness of the characters and portrayal of bars and saloons submerged in shadows cast a reflective state of post-WWII cynicism. Wyatt Earp often shouts “What kind of town is this?” in moments of hectic disturbance. The idyllic towns and cities that Earp is used to encountering as a traveling farmer is a bygone. For Ford, who was a veteran of the war, the angst shared between Earp and Doc Holliday feels personal. While the Earp brothers reside in Tombstone with a mission, a general malaise washes over them, in part due to the decay of the town’s spirit. Holliday, believed to be a figure of reverence among the community, is lonely and insecure. His threatening hostility is an artifice to compensate for his wounded soul.

What Ford understood about stories riddled with darkness and fleeting hope more than any filmmaker is that periodic moments of delicate sweetness broaden the melancholic cloud over the film. This is particularly evident in Wyatt Earp’s budding romance with Clementine, Doc Holliday’s former love interest. Earp expresses an adolescent-like awkwardness when engaging with her. As an individual who operates solely around men partaking in masculine-associated adventures, he is simultaneously comforted by and apprehensive of a flirtatious relationship. Without any explicit dialogue, viewers can sense that Earp’s affection for her is rooted in a grasp of innocence and romantic bliss amid the threat of violence that he must undergo with the Clanton family. This feeling is distilled in the scene’s closing moments, as prior to Earp riding off into the open desert following the climactic set-piece of the O.K. Corral gunfight, remarks to himself, “I sure like that name, Clementine.” The line demonstrates an effort on his part to look fondly upon something as sweet as the fruit that shares its name with his love interest.

How ‘My Darling Clementine’ Strips Away Western Idealism

John Ford’s vision of the West experiences none of the thrills expected from its folklore. The Earp brother’s victory at the O.K. Corral is no triumphant act of perseverance or justice. Wyatt Earp’s motivation to accept the appointment as the marshal of Tombstone is predicated upon vengeance, and when the vengeance pays off, nothing is ultimately resolved. All it creates is slayed people, including Doc Holliday, who survived the gunfight in real life, in a town spiraling into mayhem. While Henry Fonda is emblematic of an idyllic American with his gentle, soft-spoken dignity, he is not the courageous Herculean figure that John Wayne embodied onscreen. Dressed in an all-black attire, Earp is cold and distant from the community of Tombstone. He is a decent man consumed by the lust for vengeance. The dichotomy of the historic figure further cements the melancholic heart of Ford’s film. The director’s humanist touch allows the character to shatter preconceived notions of good and bad guys. The marshal refers to his law enforcement duty as strictly a family affair, undercutting any notions of Western justice being a force of nobility.

Modern Westerns in the wake of Ford are expected to be revisionist. The director has molded the genre so much that revisionist takes on the old West are synonymous with the general iconography of Westerns. When modern audiences envision the American frontier, they think of towns spiraling into debauchery, saloons immersed in a sinister shadow, and a cowboy/sheriff who uses their power to channel their simmering violence. Packaged with its downbeat portrayal of the West, My Darling Clementine‘s historical inaccuracy represents the system of mythmaking attached to the genre, as well as the cultural foundation of America. Ford presents a sinister Western vista lacking any concern for nobility, stability, or justice. In the end, My Darling Clementine shows that the genre and its historical backdrop is a lost cause where the truth is subjective.

Source: https://dominioncinemas.net

Category: MOVIE FEATURES