The music industry has witnessed countless transformations, reinventions, and image makeovers over the years, but nothing quite compares to the moment when Prince changed his name to an unpronounceable symbol on his 35th birthday, which happened exactly 30 years ago today.

- California Senate Approves Unemployment Pay for Striking Workers

- ‘Dumb Money’ Review: Craig Gillespie Makes ‘The Big Short’ For the Reddit Generation | TIFF 2023

- ‘Snowfall’s Sixth and Final Season Sets Release Date

- Where to Watch and Stream ‘Guy Ritchie’s The Covenant’

- Channing Tatum and Zoë Kravitz Step Out Together at Annual Caring for Women Dinner: ‘Gorgeous Night’

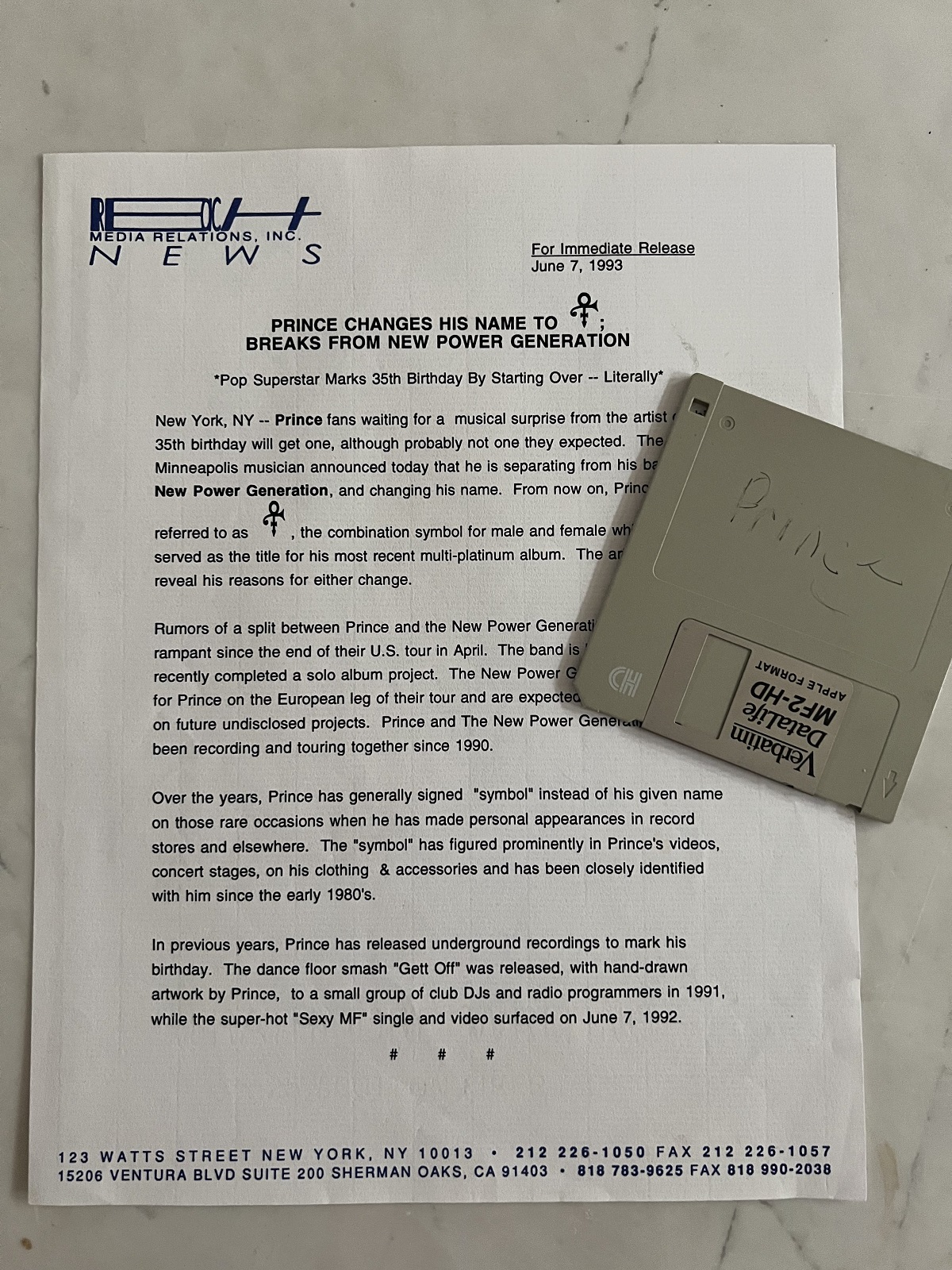

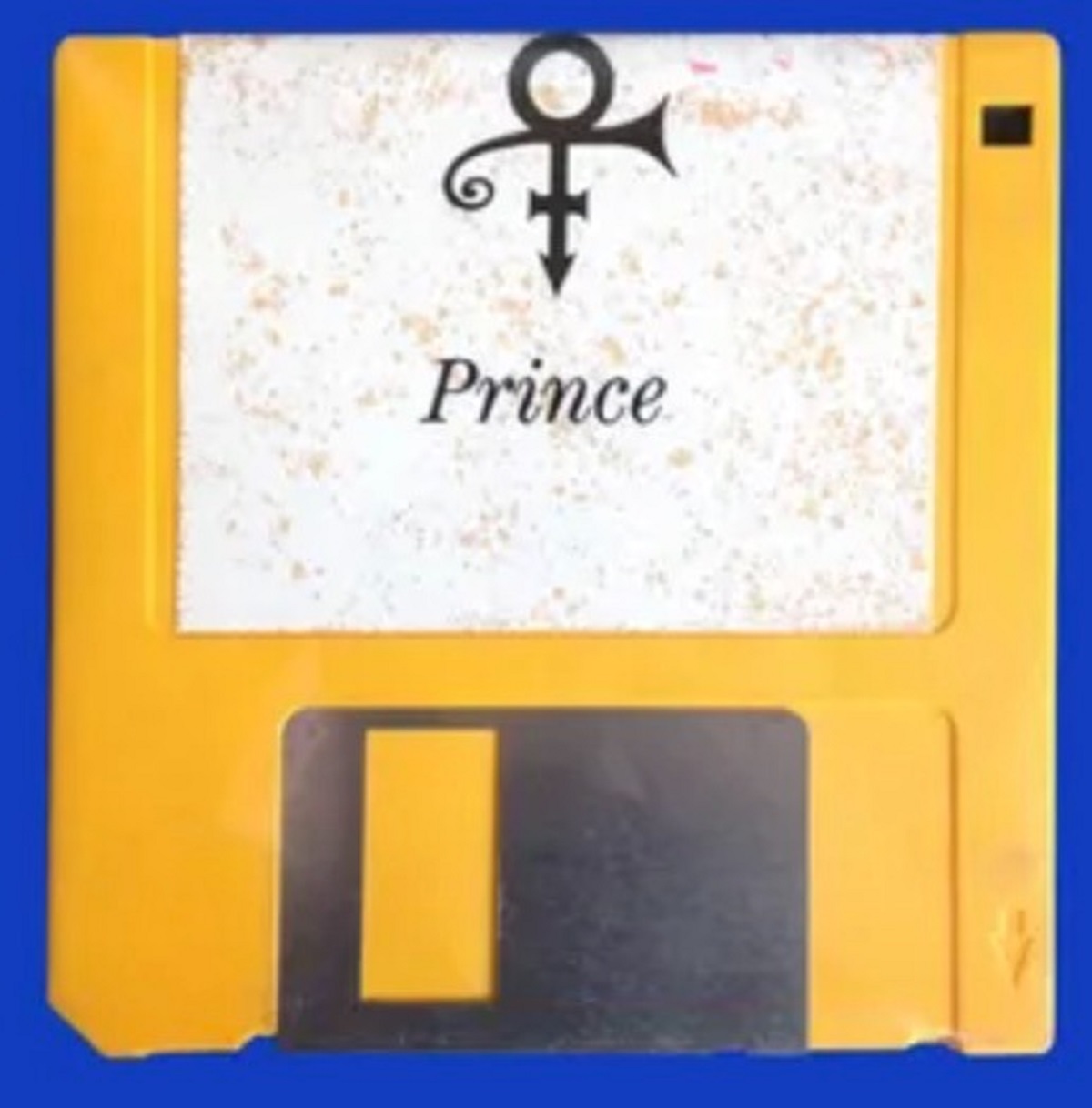

The precise motivation behind this decision was never explicitly stated, though many speculated that it might have been a strategic move to escape his contract with his long-standing label, Warner Bros. Records. Prince made the announcement through a statement that read, “It is an unpronounceable symbol whose meaning has not been identified. It’s all about embracing new perspectives and tuning into a fresh frequency.” As the symbol didn’t exist on standard computer keyboards, Warner Bros. distributed floppy discs to media outlets containing a digital representation of the symbol. However, most outlets eventually adopted the moniker “The Artist Formerly Known as Prince” for convenience.

you are watching: Why Prince Changed His Name to an Unpronounceable Symbol 30 Years Ago, and What Happened Next

Television broadcasters were also equipped with a brief video featuring the symbol, accompanied by a distinct digital clanking sound, reminiscent of the iconic sounds used by film companies when their logos appeared in movie credits.

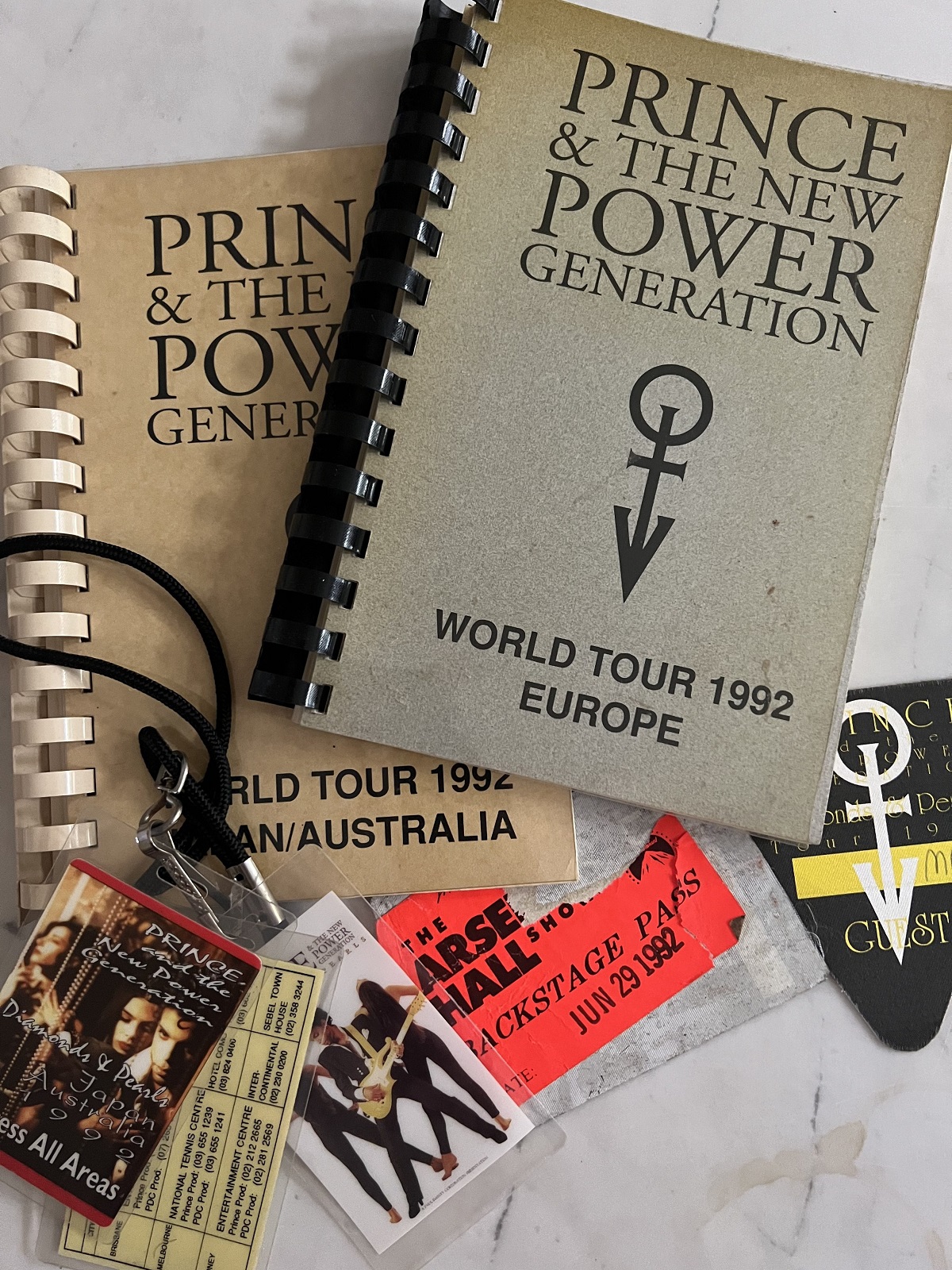

The symbol, initially a fusion of the familiar gender symbols for male and female, had made earlier appearances in a slightly different form in the artwork of several Prince albums. It first appeared on “1999” and later adorned the covers of “Purple Rain” and “Graffiti Bridge,” as well as tour laminates and similar materials. However, since this symbol couldn’t be copyrighted, Prince enlisted the services of the Minneapolis design studio HDMG to modify it, incorporating a horn-like element. He secured a copyright for this altered version and debuted it as the unpronounceable title of his 1992 album, an album commonly referred to as “Love Symbol.”

Prince had always been an artist known for his provocations, enigmatic nature, and penchant for incorporating symbols (like using an eye for “I”) or numbers (such as substituting “4” for “for”) in his album artwork. However, his decision to adopt an unpronounceable symbol marked a new pinnacle of his creative eccentricity. Was it a jest, a ploy, or a maneuver to extricate himself from his recently renewed label contract, reportedly a staggering “$100 million deal”? Or had he reached a point of artistic departure that defied easy interpretation? The answers were far from straightforward, and one can’t help but wonder if the ensuing confusion, amusement, and chatter were all part of his calculated design, whatever that might have been. Prince, in characteristic fashion, never provided a conventional explanation.

In a 1999 interview with MTV News’ Kurt Loder, he simply stated, “Very simply, my spirit directed me to do it. And once I did it, a lot of things started changing in my life. People can say something about Prince, and it used to bother me. Once I changed my name, it had no effect on me.”

In a slightly more detailed explanation during an interview with Larry King in the same year, he shared, “I delved deep into my heart and spirit, seeking a profound change and a shift to a new phase in my life.” He continued, “One of the ways I pursued this transformation was by altering my name. It was a way to detach myself from my past and all the associated baggage that came with it.” Prince acknowledged that he and Warner Bros. did have certain issues, primarily concerning music ownership and the frequency of his releases. He added, “We had some disagreements, mainly about who owned the rights to the music and how often I was expected to produce. Other than that, we got along.”

Despite Prince’s immense success as one of the most prominent artists on one of the music industry’s artist-friendly record labels, Warner Bros. was not inclined to address his primary concerns. These included his desire for more frequent music releases and the fact that the label, rather than Prince himself, held the rights to his recordings. This situation remained unresolved, especially since Prince had recently signed a lucrative new contract. Frustrated by the impasse, Prince’s discontent escalated to the point where he began painting the word “Slave” on his face. Ultimately, he parted ways with the company when his contract expired in 1996. (It’s worth noting that he later signed a new two-album deal with the label nearly 20 years later, but that’s a separate story.)

Variety interviewed Michael Pagnotta, who served as Prince’s independent publicist at the time, and Jeff Gold, who was the Senior VP of Creative Services at Warner Bros. Records and later became the label’s General Manager.

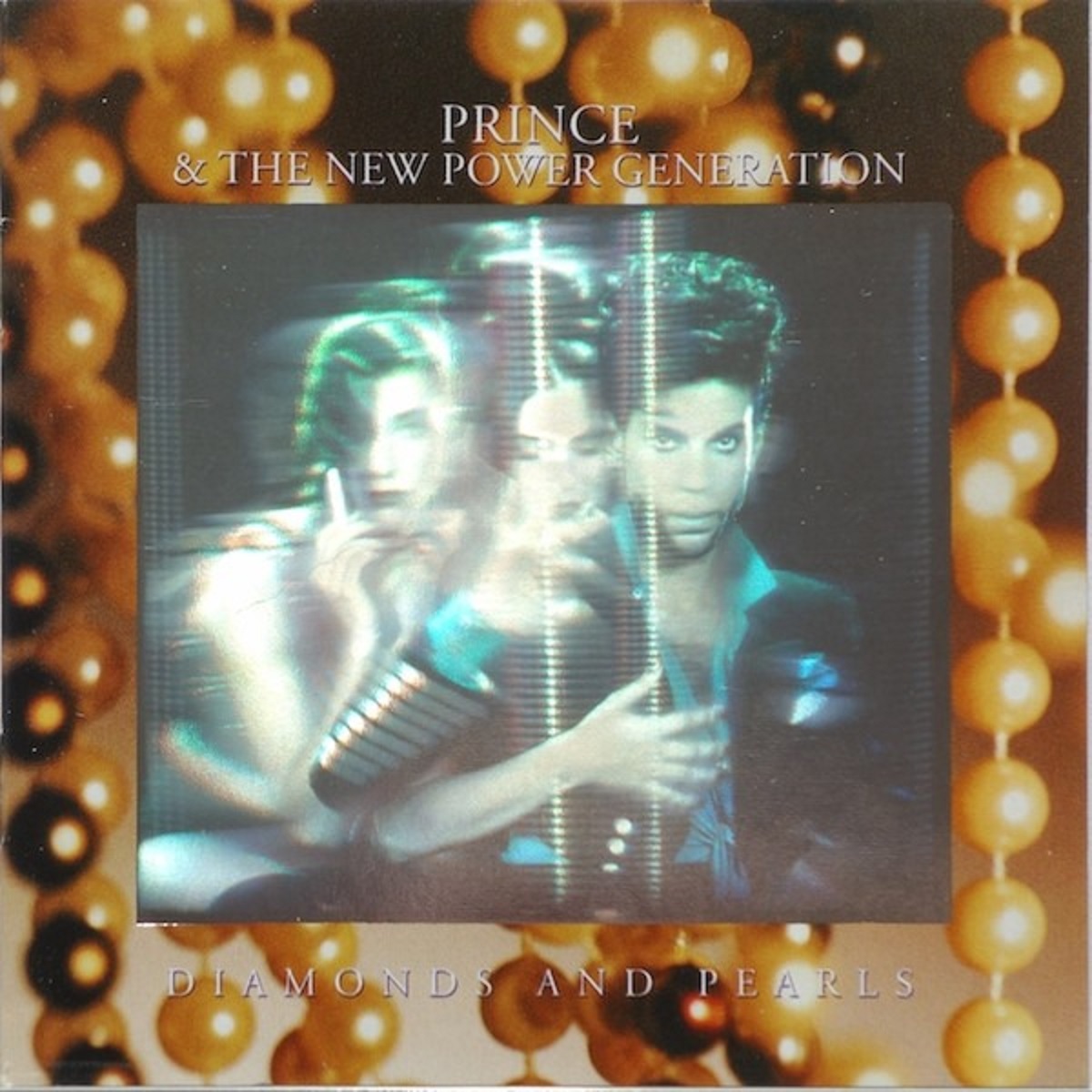

GOLD: I joined Warner Bros. in 1990, around the release of the “Graffiti Bridge” album and film, which didn’t perform well. So Warner’s top executives, Mo Ostin and Lenny Waronker, had a candid conversation with Prince. They essentially said, “Listen, you’re at a critical juncture in your career, and we can’t afford another underperforming album. Collaborate with us, and we’ll support you.” Prince agreed, and they, along with top executives Michael Ostin and Benny Medina, essentially took on the role of A&R for his next album. Over time, they started to feel optimistic about it, and that album turned out to be “Diamonds and Pearls.”

Prince submitted the album cover he wanted, which featured a close-up shot of his face with a unique hand gesture—his fingers forming a reverse peace sign, with his tongue between the two fingers, a gesture that carried a certain provocative connotation.

I examined this artwork — despite being a huge fan, I found it quite absurd. So, I conveyed this sentiment to Lenny, and he suggested, “Go have a meeting with Prince and tell him.” He arranged the meeting, and I found myself in Benny’s office, a dimly lit space with curved walls, devoid of windows, featuring two couches positioned to face his desk. Prince was seated on one couch, and I took a seat on the other. Benny introduced me, saying, “Prince, Jeff is our new Creative Director, just joined us from A&M Records. He believes your album cover could use some improvement.” It’s worth noting that in all the times I encountered Prince, he was always ready to step onto the stage, complete with his signature hair, makeup, and stage attire. On this occasion, he was wearing a translucent fuchsia shirt with pink pinstripes, paired with fuchsia-like ski pants featuring loops around the bottoms of his boots. Just as Benny had delivered the critique, his lawyer began pounding on the door, urgently demanding to see him. Benny promptly left the room, leaving me to face Prince alone.

“So, you’re not a fan of my album cover, huh?” he responded, his tone unmistakably confrontational. “What’s your suggestion then? Should I start wearing overalls like R.E.M.?” He actually said that, adding, “No, seriously, I believe you can come up with something better than that.” It was an excruciating meeting, with Prince refusing to budge an inch. He was well-versed in using silence as a form of pressure and expertly pushed back against my feedback. This back-and-forth continued for approximately half an hour until he finally asked, “Show me some of the album covers you’ve designed.”

see more : The 10 Best Original Song Oscar Winners of the Last Decade, Ranked

I promptly went to my office and retrieved a stack of CDs featuring designs I had created during my time at A&M Records. I handed the pile to him, and he proceeded to offer dismissive comments about each one, calling them “terrible,” “outdated,” and questioning if he should aim to resemble any of them. However, as he neared the end of the stack, he came across a hologram special package I had designed for Suzanne Vega, an artwork for which I had won a Grammy. Prince stopped and examined it closely, remarking, “This is really impressive. Why can’t I have a hologram?”

In short, we arranged a photoshoot for the hologram, and when I presented a glass plate sample to him along with Benny, he was genuinely pleased with the result. He then suggested, “What are you doing right now?” I replied, “Heading back to the office.” Prince responded, “Why don’t you guys sit on that couch,” and proceeded to perform for approximately 45 minutes to an hour, with us sitting about 15 feet away. It was truly one of the most memorable experiences of my life. After that, I became one of the maybe five people he would actually converse with at Warner Bros.

PAGNOTTA: I began my career as an agent, booking figures like ’60s activists Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin for college lectures and similar events. So, right after graduating from college, I had experience dealing with challenging clients. Later, I joined Rogers and Cowan, a public relations firm, and while there, I crossed paths with a colleague named Jill Willis. She had been handling some publicity work for Prince, and he eventually brought her on board at Paisley Park, sometimes shifting roles in the organization. After I had started my own firm, Jill hired me to handle publicity for a couple of artists, namely saxophonist Eric Leeds and singer Ingrid Chavez. Ingrid found herself in a complex situation involving Lenny Kravitz and Madonna because of her co-writing credit on “Justify My Love,” which was originally uncredited. I believe Prince appreciated how I handled that situation, and Ingrid ultimately emerged in a favorable position. Consequently, I was entrusted with the Prince account just six months into running my own business.

The initial meeting I had with him was quite memorable. I was flown to Paisley Park, and I recall he was on stage, presumably rehearsing. He strolled across the stage, and someone there introduced me, saying, “This is Michael Pagnotta, he’s your new publicist.” Prince extended his hand, shook mine, and continued walking without turning his body or making eye contact. That marked my first encounter, and, for the most part, every subsequent interaction followed a similar pattern—almost like he would magically materialize and then just as swiftly vanish, as if performing a disappearing act. I’m sure you’ve heard about that. You could be in one place, and he’d be there one moment, only to disappear the next, resembling some kind of magician’s trick. His mode of communication was akin to the Riddler from “Batman.” During my early 20s, I worked for him and was perpetually on edge, feeling somewhat terrified throughout my tenure.

PAGNOTTA: The album was a massive success—people tend to forget that “Diamonds and Pearls” ranks among Prince’s top-selling records. Then came the tour: first in Europe, Asia, and Australia, with the U.S. leg scheduled for the following year. It was stipulated in my contract that I had to be wherever he was, and it was quite a tense experience. He would, at times, quiz me about the songs he had performed that night, and you could never predict whether he might want to perform at a club immediately after the main show. You had to perform exceptionally well, because if you didn’t, you knew there was a plane ticket waiting for you to head back home. I was convinced I was on that plane a few times!

Nevertheless, the tour went exceptionally well, with reviews that were absolutely outstanding. But when I returned home, I started hearing these peculiar murmurs about a conflict between Prince and Warner Bros. However, that all changed when he signed that “$100 million deal.”

In the early ’90s, there were several substantial deals—think Michael Jackson, Madonna, R.E.M.—and naturally, Prince had to secure the most significant one. So, we drafted a press release, piecing it together, stating it was a “$100 million deal.” However, hardly anyone delved into the fine print, which stipulated that he had to sell 5 million copies of each record to trigger the next $10 million advance. In reality, that figure was rather misleading. But hey, it’s the music business, right? For a brief moment, it appeared as if everything was going smoothly. Yet, Prince soon encountered obstacles because the label was hesitant to release records as frequently as he desired. How can you accommodate a major artist who wants to release an album every three or six months? The logistics simply couldn’t support such a pace.

GOLD: He had been vocal about wanting to regain control of his masters, and Mo’s response was essentially, “You should have considered that before you renewed your contract.” Then one day, Mo walked in and said, “Prince has changed his name.”

PAGNOTTA: At some point in the late spring of 1993, with almost no prior notice, we received a call: Prince was changing his name. There was a moment of stunned silence. I eventually asked, “To what?” The response was “The symbol.” Now, I understood what that meant because, during our tours, he had asked me to take a video camera into the middle of the arena a couple of times. On one occasion, he gave me a small metal version of the symbol from one of his custom-made jumpsuits and said, “Ask people what they think this represents.”

Responses varied, with some people interpreting it as love or unity. However, a substantial 80 to 90% of the individuals I asked—regardless of age or gender—said it represented Prince. He had been using this symbol since “1999,” so people had become familiar with it. Once he realized the depth of his association with that symbol, it probably motivated him to proceed with the change. We quickly assembled a press release, and I crafted some narrative about a phoenix rising from the ashes or something to that effect.

We distributed the floppy discs containing the symbol and even created a video where it would transition from the background to the foreground, concluding with a metallic clank reminiscent of a “Current Affair” type show. Despite the time constraints, the execution was quite well-planned.

GOLD: Prince was known for his constant unpredictability—his reputation was “Expect the unexpected.” However, it quickly became evident that he was adopting this change so that he could assert, “Well, you guys signed Prince, but I’m no longer Prince; I’m the symbol.” Of course, that notion wasn’t going to hold, but we decided to embrace it with a sense of humor—although, oddly enough, this only seemed to irritate him further. It was just another one of Prince’s eccentric moves, and we saw it as an opportunity for a publicity stunt to garner some attention, right?

At times, it turned rather amusing because the folks at Paisley Park, who were, to some extent, apprehensive about their boss, would ring us up and say, “My boss is on the phone for you.” And we’d playfully ask, “Who’s that, Prince?” “Well, my boss.” “Who is your boss?” We were just teasing them in good spirits.

The media was having a blast with it—the whole “The Artist Formerly Known as Prince” and the typographical abbreviation. But in reality, it was just another one of his eccentric moves. When we discussed the next album—which has since been retroactively referred to as “Love Symbol”—he mentioned, “I just want this symbol; I don’t want my name on here.” We collaborated on all these ideas with him, and it was all quite good-natured, even though he was making public statements about feeling like a “slave” and Warner Bros. mistreating him. He was essentially the same person I had been dealing with.

PAGNOTTA: The MTV twist to this story is when Linda Corradina, who I believe was their news director at that time, called me while laughing. “I know you’re known for being a bit wild, but this, this is insane! What are you doing?!” It felt like a consolation chat because honestly, I truly thought my career was in ruins. However, we weathered all the initial ridicule, and surprisingly, some people found it rather intriguing—quirky, but intriguing.

GOLD: At one point, he was in my office, griping about how Warner Bros. wouldn’t permit him to release all the albums he wanted to release. He essentially proposed, “Let me depart from the label and fulfill the contract by just delivering a slew of music” (which is essentially what he ultimately did). He knew precisely what he was up to, and he was aware that we knew too. So I told him, “You know, we paid you a substantial amount of money for each of these records as an advance, and we need the flexibility to market them, release two or three singles, and allow some space in the marketplace between them. We can’t just churn out a record every three months.” That was one of the rare moments when he dropped the act with me. He responded with something like, “You’re aware that everybody perceives these albums as carefully crafted, conceptualized works, right? I’m constantly in the studio, and when I accumulate enough songs that I think, ‘Hey, together, this makes a record,’ it’s a record. So I’ve got a lot of material, and I want to release a lot of albums.” It was one of the few times we had a genuine conversation, as opposed to one of those quasi-theatrical performances he was renowned for.

It never escalated into a dispute between any of us—perhaps there were disagreements between his lawyers and the business affairs teams. However, Prince primarily communicated through press releases, and he still made appearances at Warner Bros.’ offices, even during marketing meetings, with the word “slave” painted on his face! Nevertheless, there was never a period when he refused to converse with us, and I could always reach him by phone.

Approximately five years after he left Warner Bros. in 1996, Prince returned to using his original name, Prince, which he retained for the remainder of his life. He continued to release albums at a rapid pace, often producing two or even three per year. However, he never quite reached the commercial and critical heights he had achieved in the ’80s and early ’90s.

PAGNOTTA: I suppose at some point, he realized that the change wasn’t really working, neither from a legal nor a personal perspective. In the late ’90s and early 2000s, he entered a challenging period where he released as much music as he desired, but nobody seemed to pay much attention. So, he reverted to being Prince and began performing his hit songs again, resulting in tours that generated millions of dollars.

It’s one of those moments in recent music history that nearly everyone remembers, whether they found it funny, brilliant, or absurd. One of the world’s most famous musicians essentially erased their own identity and transformed their name into an unpronounceable symbol? It was so outlandish and unprecedented, yet simultaneously felt incredibly modern in some way. Prince was an enigmatic individual. He would say things to me, and I wouldn’t grasp what he meant at the time. However, months later, I’d suddenly understand, like, “Aha, that’s what he was referring to.”

Back then, of course, it appeared to be the most ludicrous thing anyone could do. But now, it seems genuinely historic.

Jeff Gold is now a music historian and the proprietor of Recordmecca, specializing in top-tier music memorabilia and collectibles. Michael Pagnotta is an artist manager and the owner of Reach Media, a publicity and marketing firm.

Source: https://dominioncinemas.net

Category: MOVIE