The production designer’s job is always a challenging one. Studying the script and understanding the vision in order to recreate it for camera isn’t simple, but imagine being assigned the once-in-a-lifetime responsibility of putting J.R.R. Tolkien’s timeless Middle-earth onscreen in an era no one has ever seen before. For Prime Video’s massively ambitious series, The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power, that’s exactly what Ramsey Avery was hired to do: conceptualize and build the Second Age of Middle-earth, from the text up. In an exclusive interview with Collider’s Steve Weintraub, Avery takes us on a deep dive into the endless details, information, and influences that inspired the golden age of Tolkien’s Númenor, Khazad-dûm, and more.

- ‘Muppets Mayhem’: The Electric Mayhem Spread Wisdom on Their New Album and Its “Melodious Confection” of Tunes

- Here’s How Maddie Ziegler Booked Her Role in ‘West Side Story’

- ‘Star Trek: Strange New World’ Season 2’s Showrunners on Setting the Tone for the ‘Lower Decks’ Crossover

- ‘The Other Two’ Star Drew Tarver Talks Cary’s “Fully Opportunistic” Direction & What More to Expect This Season

- Wood Harris on ‘Shooting Stars,’ the Inherent Conflict in Sports Dramas, and the Superstardom of LeBron James

You’ve seen Avery’s eye for building worlds in films like Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report and A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, where he first started out as contributing art director, and you’ve watched in awe as cosmic journeys played out across his designs as supervising art director in Star Trek: Into Darkness and Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2. For Rings of Power, Avery says he and the crew “needed to dial back from that period of decay and make things as glorious as we possibly could,” in reference to the Third Age of Middle-earth, the one Peter Jackson’s trilogy laid the foundations for in audiences’ minds. He tells Weintraub it was about studying the lore, analyzing the architecture of the existing art, and then tracking it back thousands of years, based on Tolkien’s texts and inspirations. Rings of Power Season 1, which stars Morfydd Clark, Ismael Cruz Córdova, Charlie Vickers, and more, really is a cinematic masterpiece and a testament to Avery and the cast and crew’s dedication and talent.

In their interview, which you can read in full below, Avery addresses the highs and lows (that ended up being highs) throughout production, from adapting to the conditions of a pandemic to working with the natural flora of New Zealand. Being the largest project Avery has worked on to date, he shares with us just how much concept art was being produced per day, the actual villages and built-to-scale structures the crew constructed, like Captain Elendil’s (Lloyd Owen) ship, as well as what surprised him most about the job. Avery also talks about his experience working with Spielberg, his theme park designs, which project was the only one to make him cry, and why working on Marvel’s upcoming Captain America 4 is so different from all the previous Marvel productions.

COLLIDER: Earlier in your career, you got to work with Spielberg on Minority Report and A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, and I’m curious what that experience was like for you being new to the industry and working with such a titan?

RAMSEY AVERY: It was really remarkable. I was very, very fortunate to work with two very different production designers on those two movies; Rick Carter on A.I. and Alex McDowell on Minority Report. They have very different processes in terms of how they do their design work and they have different emphases. So they’re both working with Spielberg, and how that filters down into the art director world had different repercussions, but what’s really interesting in both of them, A.I. was actually the first feature that I worked on, and in both cases, I was given just a lot of leeway. There was one point, actually, Rick called me at seven AM in the morning, and said, “I need to ask you to design a little set and present it to Spielberg in three hours. Can you do that?” [Laughs] So I was like, “Uh, okay!”

It was a great opportunity for me because I was working with really good people, and his people, you know, it’s a very strong, well-organized machine. They know what they’re doing, the ADs are great, the producers are great, they all know kind of what he’s looking for. He was very engaged, so we’d get to have meetings and have time with him and get to ask a lot of questions, and he’d answer the questions with a lot of grace. Then I actually got to spend time on set with him, watching him, how he worked, and how he thought through things. And it was really kind of clear to me, it felt to me like he had the movie in his head; it was just all of our jobs to get it out, then he could just play things, and when things weren’t quite in front of camera the way he wanted to, then asked us to help him figure out how to get the right things. So, it really was, for my first feature to be able to work at that level, insane and really educational, and just really great people. All of them were really nice people, and a process that just kind of knew how to make a movie.

I’m imagining that you’ve worked on things, and while you’re working on something, you’ve been offered something to go work on something else. Is there a project that still hurts that you had to turn down because of whatever reason?

AVERY: Oh, I had a chance to go make a commercial in Greenland, and I’ve always wanted to go to Greenland [laughs], and so that one I feel a little bit, “Mmm.” But for the most part, I think in terms of actually turning down opportunities, feature-wise or TV-wise, I’ve been able to kind of balance things along the way. I mean, I don’t know what I don’t know. There are things that my agents may be getting calls for that they’re like, “Oh no, he’s busy,” so I don’t know. But the things that, in terms of what I’ve wanted to do, I’ve been fine.

There’s a couple of times in my career, for various reasons, I’ve done a lot of theme park design, like about a third of my career has been in theme park design. So there will be times when I will, for whatever reason, jump off into theme parks and then feel like I have to kind of get the whole machine up and going again to get back into film, reconnect with everybody and say, “Hey, I’m here, I’m here!” So that’s always felt like that took a little bit of extra time, and maybe some of that, if I wanted to keep moving forward in film and TV, I maybe should not have done that, but I also got to design the Avengers Campus for Disney, so I’ve had some great opportunities.

I was actually working on the E-Ticket ride for them, for the new Avengers ride, when– That’s the one time, when Lord of the Rings came along, I was like, “Avengers E-Ticket or Lord of the Rings?” [Laughs] That’s a ridiculous choice to have to make, who gets in a position where you get to make that choice? And it was just, it was crazy. But in the long run, at that point what I wanted to do was Lord of the Rings; it was a chance to go to New Zealand and something that I’ve always cared about deeply since I was a kid, so that was the choice. But I don’t think I’ve ever said I couldn’t do something and then felt bad about it afterwards that I remember at this point anymore.

As you mentioned, you did Avengers Campus, but I believe you also did Marvel’s Dubai Land. What is the difference between designing something in Dubai and designing something at Disneyland?

AVERY: Well, there’s just some cultural things, clearly. That was in 2008, so that culture has shifted and has become more open and more Western over time. I mean, there’s just the logistical elements… you have to design a roller coaster that can withstand a sandstorm. That’s a different thing than you have to worry about in Anaheim. In Orlando, you have to worry about hurricanes, and in Anaheim, you have to worry about earthquakes. So there’s something that you have to think about, engineering-wise, to have to deal with, but there was certainly the issue, when you’re thinking about rides– a simple thing is that witchcraft is really foreboden, right? You just don’t express witchcraft, so you can’t really have the Scarlet Witch. Particularly because this was actually, pre-Disney having bought Marvel, so we were really, at that point, working from the comic books, not from any movies. So there were issues with, how do you present Doctor Strange, how do you present to Scarlet Witch? Can you make a clear case that she’s all about manipulating probabilities as opposed to magic, and how do you play that? And certainly you think about issues of separating men and women and women with kids, separate from parents, and how you on and off-load a ride has a very different kind of sensibility than you would worry about, necessarily, in the States or Western Europe. So there were both cultural things and logistical operational things to take into account.

I will say, one of my favorite things about that whole project is that – I wasn’t in the meeting – our executives came back from a meeting with Kevin Feige and… the guy, who at that point, was his boss, and Kevin, in that meeting back in 2008, said, “You know, I want you all to understand this, that within 10 years Marvel will be culturally as important as Star Wars.” And we all went, “Okay, that’s fine. Nice to hear.” [Laughs] Sure enough, 10 years later, he was absolutely right.

Yeah, he was thinking ahead back then, for sure. You mentioned how you have to design something at a theme park in Anaheim for earthquakes and in Orlando for hurricanes. I know you’ve designed these, you’re probably a little bit biased, but if an earthquake were to hit on a ride in California when someone’s on the ride, are you solid that this thing is gonna withstand it? How do you actually factor in a 7.0 earthquake when the ride is going, or is it almost impossible to design?

AVERY: Well, the ride that I was working on, which I won’t be able to say a whole lot about – the E-ticket for the Avengers – had a big ride system in it, and I can tell you that part of the reasons that the cost on that project was so extreme was because of those architectural concerns. Like, how do you build the building to make sure that it stands up, and then there’s a ride mechanism, and the footings, and the structural support, and the bracing that was all going into making sure that it met the proper codes? And Disney doesn’t design to the state code or the federal code; Disney designs to Disney’s codes, which are a much more extreme level of engineering for multiple reasons. So, you really are designing as best as you possibly can. Like you said, I mean, if a 9.0 earthquake hit LA, all bets are off, but there is a level they’re designing to, to be as secure and as safe as they possibly can, and it comes at a cost. That’s one of the reasons why designing for Disney is so expensive, why their theme parks are more expensive than almost any other theme parks, because they put all of that extra protection and engineering and thought into the process.

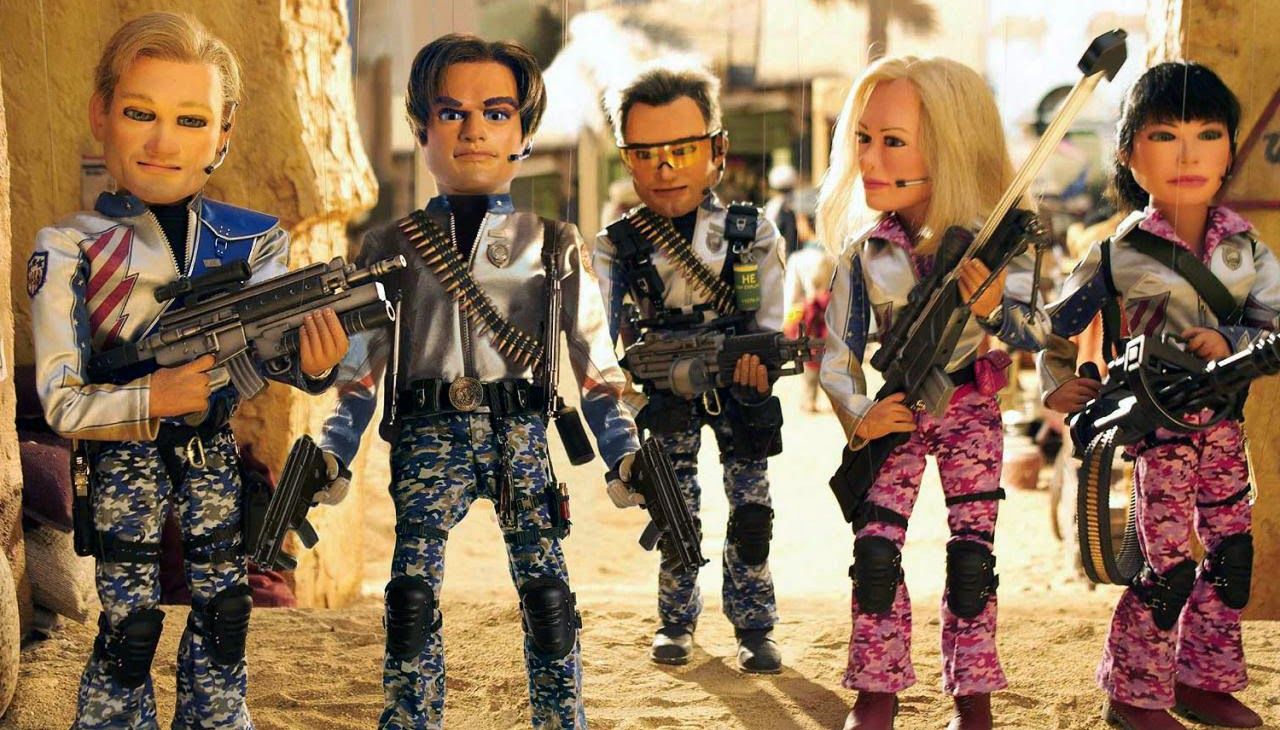

Yeah, it’s also why you don’t hear about accidents at Disneyland. You worked on Team America: World Police, which I love. We definitely have to talk about what it was like working on that one.

AVERY: That’s the only project that has ever brought me to tears, and they weren’t tears of joy [laughs]. That was the one of the most complicated things I’ve ever done. Not only are you basically building a world from scratch, but we had the extra– well, you know, everything is third scale, but it’s not really a third scale because we were working at all types of miniature scales depending on the scope of the scene that we were trying to make. But essentially, everything in the main world were basically an American Girl doll scale on that. Basically, it’s a third scale. And so the studio says, “Well, everything’s a third the size, so it should cost a third less, right?” Yeah, no, it doesn’t work that way.

Then there was a whole complication where, for various incendiary reasons, we ended up with a production designer in Los Angeles who Matt [Stone] and Trey [Parker] wanted to be their guy. Then the executive producer wanted to have a separate designer in New York, so he brought in David Rockwell as a visual consultant in New York, and David brought in his theatrical designer, the guy that he had doing Broadway shows with him as kind of his key visual person, and essentially two different movies were being designed. There was Matt and Trey’s movie in Los Angeles and there was David Rockwell’s Broadway movie in New York, and I would get two sets of drawings on my desk, and as a supervising art director my job was to figure out how to get that in front of camera.

Toward the last six or eight weeks of the project, we had six separate units working simultaneously at various scales, and everything changing, and Matt and Trey, I mean, I really, really loved working with them, but they don’t plan, that’s their whole process, right? They want to be in the moment, so we were constantly changing things as the new ideas came up, with six units and two different designers. And yeah, there was one morning that just… I broke [laughs]. I came back, but there was a moment.

In other words, there was a day when you were working on this one that you’re like, “I’m ready to rage quit. This is too much.”

AVERY: Pretty much.

The movie turned out great, but yeah, getting there, it sounds like it was not a pleasant.

AVERY: But it still was such a hoot to be able to work in that world, and to work with Matt and Trey, and the the clever things where we could try to figure out how to do stuff like Kim Jong-il’s town we built in Chinese take-out scale. So we actually figured out how to build houses out of take-out boxes so that his whole village, perched in the mountains, started with a regular scale of a take-out box, and then we printed smaller versions of that to make it recede in distance in camera. It was a really wonderful opportunity to work with very little visual effects. It’s mostly in camera and working with theater effects to do foreground miniature work, or to do forced perspectives, and playing with different scales with different figurines, and all of that was really quite a blast.

Yeah, it’s a shame, I don’t know how many of those sets were saved. I always wish more sets from things like that were actually saved, but I would imagine it takes up a lot of space, they’re not designed to last, all of that.

AVERY: Yeah, that’s for sure. I don’t think anything from that actually got saved. I think at one point a lot of the vehicles were saved for quite a while, but who knows where they went to. Into the bowels of Paramount storage, you know?

I would imagine there’s a lot of people who know a lot about the making of Rings of Power, and there are other production designers that know a lot about production design, but what do you think might surprise fans of the show to learn about the actual behind-the-scenes of the making of the first season, and might surprise other production designers?

AVERY: I think the thing that surprised me the most, in the long run, was that we went to New Zealand because that’s Middle-earth, right? New Zealand is Middle-earth, and there’s all of that. I spent the first month that I was there basically [in] planes, boats, helicopters, cars, seeing a lot of New Zealand, which was a wonderful experience, but in the long run because of the weirdnesses of filmmaking, we had a shorter period of time. Peter Jackson had years to put the three movies together, and even he, over time– you’ll watch the movies and they become more and more visual effect-y because it’s expensive to take a crew out in the world, and it rains. In New Zealand, it rains a lot. So trying to manage a location shoot really became problematic.

In a lot of cases, we just didn’t go on distant location. We shot a lot of it within 30 miles of Auckland, and combining that with the idea that the showrunners were insistent that as much be in camera as we could possibly make it, we had to figure out how to find locations around 30 miles of Auckland, which is a lot of pine plantations and sheep paddocks. There really aren’t any forests, per se, in New Zealand. There’s certainly no Northern European, English forests in New Zealand; there’s what they call the bush, which has a bunch of palm trees and fern trees in it. Even the pine plantations have small palm trees, Nikaus, and Pongas are these tree ferns that infest the pine plantations, so everywhere you look, the forests look like jungle, they don’t look like old Europe, or what we think Middle-earth should look like. So, trying to figure out how to get things in camera and not chop down the native trees – because you don’t wanna do that – and then make this still look like we’ve traveled the breadth of Middle-earth, and keep it in camera and not just rely on visual effects, that actually took an awful lot of work.

You guys were making this show during COVID, how did that actually impact you? There was a whole period of time where shipping and planes and everything was closed down. I don’t know the time frame of when you were designing, and maybe you can illuminate that, but I would imagine there’s times where you would normally be ordering something from somewhere and maybe you couldn’t order because of COVID?

AVERY: I started, for various reasons, about halfway through the prep, which was in the end of August, beginning of September of 2019, so we actually were filming. We were aiming to film the first block, which was Episodes 1 and 2, starting in the end of January, and things, as they do, pushed a little bit. We didn’t really get started filming until March of 2020, so as you can imagine, we didn’t get very far in our filming. One thing that helped us in all of that is that it became kind of clear, as I was getting into the weeds of how to get all this to happen, that the original schedule where we were gonna do block one, block, two, block three, and just shoot all the way through, was simply not going to be able to happen. We weren’t gonna be able to produce the amount of scenery, the amount of costumes, the scripts weren’t going to be necessarily as ready as they needed to be to work on that block, and Amazon wanted to know what was happening in Season 2.

So we had actually pushed an idea about taking a hiatus after we finished block one, and we had built in this two-and-a-half month hiatus period into our schedule; we were gonna separate block one from block two and three. As it happened, we ended up taking that hiatus as COVID time. So basically, we got to shoot two weeks and then COVID, and everybody who wasn’t a New Zealander went off to their various places in the world. Some people stayed, several of the actors stayed, some of the artists stayed, we all kept working. We all went to wherever we were in the world and we kept working, all the way through the COVID process. Because it was New Zealand, and because they were smart about the whole process in a way that they could because of an island nation, they were able to get us back and working and building. We were building within eight or nine weeks again, and so we were able to get ourselves up and going, and pretty much back on schedule.

Some things were nice about that. That meant that Tirharad, our village, got to sit out in the weather for an extra three months, so that was cool. You know, got some real nice aging, some natural aging on it, which was great. Once we went back, then that was it, we were there. People did not come and people did not go. Things did not come into the country. On every major project I’ve ever worked on, you get to the point, two-thirds of the way in, where you just need more people, that everything has piled on top of itself, and you don’t have enough sculptors; you don’t have enough greensmen; you don’t have enough painters; you don’t have enough carpenters; you don’t have enough prop makers, you just need more people, and we couldn’t get them. There was no way to add more people. So that meant that we had to make choices where we had to scale back expectations or figure out how to reuse one thing to make it into another thing. We had originally designed an entire original set for Celebrimbor’s forge, but because we couldn’t get enough people in to build that set, we had to actually repurpose an existing set, kind of at the last minute, to take what was the Hall of Lore became the dungeon, became Celebrimbor’s forge, so that there were levels.

I was going to say, I noticed, and I was very angry at the reused— I’m joking!

AVERY: [Laughs].

I love the show and I’m really amazed at what you guys were able to do with your back against the wall.

AVERY: The other thing to go to New Zealand for was that those crews are spectacular crews. They really are. We were working with people that either had worked on the Peter Jackson movies or we were working with the kids of the people who had worked on the Peter Jackson movies. So there’s this built-in DNA of Tolkien and Middle-earth that exists there beyond the fact that they’re just– the craftsmanship is amazing, world class, as good or better of anything I’ve ever worked with anywhere else I’ve worked in the world. And just good people, just really great attitudes, and it really was, I think that was a saving grace. Between the fact that we got to kind of live our lives, more or less, once we were let out of the– we weren’t even en masse. I mean, the 40,000 people in a rugby stadium when the rest of the world is kind of locked in their bedrooms… So it was a very different environment, but it was us, it was just us. But because those crews are so good, I think that’s the other thing that got us through that.

So you had to design the Second Age, which has never been seen, it’s all new. So what ended up, for you, being the big challenges of the Second Age and trying to make sure that while the design is new, it also fits in with what people know?

AVERY: There’s so much art and there’s so [many] different expectations. You go all the way back and Tolkien had drawings of his own. When he was coming up with the books, he did drawings and he did paintings, and they’re really interesting, striking imagery, very graphic, and very strong. You go all the way through all the various artists. When I was a kid, it was the Brothers Hildebrandt, that’s what Middle-earth looked like, it was the Brothers Hildebrandt. Then you had Ted Nasmith, then you had a little bit of Roger Dean, and then you get into the Alan Lee and the John Howe version of it, which became kind of codified in the Peter Jackson movies. So there’s this arc of existing art.

Our job was kind of, I guess, threefold. One was, what’s the DNA in all of that, that when you look at it, you know you’re in Middle-earth? What makes that different than [Dragonriders of Pern] or Game of Thrones or [The Chronicles of Narnia]? What are those elements that tell you you’re in a fantasy place, but it’s not another, it’s specifically Middle-earth? And so we had to kind of figure out what that characteristic of, what’s that epic quality, but what’s that really grounded quality? One of the things I say a lot is that when you read Lord of the Rings, sometimes you know exactly what they had for breakfast; there’s that level of specific granular detail, and that’s something that we really wanted to make sure that we had.

How did that translate, then, into the Second Age? Well, the Second Age is an age that represents, in almost all of the races that we’re dealing with, the best they’re ever gonna be. It is not the Third Age where that’s kind of the apocalypse. It’s faded – 3000 years later and everybody’s fading, and that’s what we have in our heads from the movies, and in some degrees, from most of the artwork, because everything kind of focuses mostly around Lord of the Rings, not the [Unfinished Tales] or The Silmarillion, or some of those other books. We really think about the Third Age, which is a period of decay. So we needed to dial back from that period of decay and make things as glorious as we possibly could. Then trying to figure out what that means, like, in some cases, a “golden age” can mean it’s literally gold, so let’s find a way to make the Elvish forest, rather than the darkness that we see in Galadriel’s forest in the movies, let’s make it bright and literally golden. So the trees are birches or aspen so that they’re always in gold. And funnily enough, when you go into the words of Tolkien, you find that his trees are gold all the time. You know, if you look back into how he describes trees, they’re always golden trees, so that was a legitimate kind of, “Oh, Tolkien talks about his golden tree, so let’s make Lindon out of golden trees.”

And so it was a series of finding, for each of those cultures, what’s the signposting that makes it specific to the Second Age? What makes it glorious? What makes it epic? What makes us know that we still have the elements that we’re gonna see that we know exist in the Third Age? And so, there were very specific things I looked for, some of the architecture that was in the movie. There’s echoes of Elvish arches that we didn’t have the exact version of. We kind of felt like the Elves in the Third Ages, both the elves and the Dwarves in the Third Age, had gotten kind of to the point where they were so much hanging on that they almost kind of went over the top. Literally, we know the Dwarves dug too deeply and too greedily, and that’s what happened when the Balrog appears and Moria gets destroyed. So that’s the architecture we’re seeing in the Third Age, overdone architecture, so let’s bring that back. And so, the Elves were much more of nature in our world than they were in the Third Age. The Dwarves are much more of stone. Rather than making big sculptures themselves, and giant bits of architecture, every bit of architecture we did for the Dwarves you could still feel the stone. In fact, things come out of stone and go into stone, there’s very little where it’s just architecture, there’s always stone in the design of that world.

So it was really trying to figure out those beats, and strangely enough, that’s one of the things with the crew that, you know, when I talk about people who worked on the movies or their kids worked on the movies, there was actually a little bit of deprogramming that we had to do. It was like, “We’re not doing the Peter Jackson movies. We have to go back and figure out what that Second Age looks like,” but because they had the DNA inside of them, of all of that, that element was still there, and it informed and blossomed into the things that we were trying to do specifically with our stories.

see more : How ‘Past Lives’ Director Celine Song Got Complete Authorship on Her First Feature Film

One of the things about Rings of Power is that it’s essentially an eight-hour movie, and I’m just curious, what was it like for you trying to work on a series that massive? Because it may be the biggest thing you’ve worked on in terms of how much you need to do.

AVERY: Yeah, it’s definitely the biggest thing I’ve worked on, and I mean, bigger than I think anybody had done singularly, even in New Zealand. I mean, it was a really big project. Like you said, it’s an eight-hour movie, and there are edits for each of those episodes that was another half hour. So we really produced a 12-hour movie that got edited down into an eight-hour movie. There are whole sequences and whole scenes and things that I’ve cared passionately about that didn’t make it into the final edit. It’s just the nature of the beast, you know, you got to fit in the time and tell the story you gotta tell. The only way to do it is one step at a time. We started back and I concentrated on the things that we had to concentrate on for Episodes 1 and 2. So figuring out what the Dwarves and the Harfoots and the Elves and the Southland, what is that? And concentrated on that, didn’t get into thinking about Númenor right away or the Orcs, or Eregion. So trying to figure out what those worlds were with a bunch of reference and a lot of art. We had, I think at the highest point, we probably had 30 illustrators, concept artists, working all around the world, and some set designers doing modeling work.

There was a point where, really for almost more than a year and maybe up to a year and a half, where somebody, somewhere in the world, was always working in our art department. There was always somebody working to try to just generate enough visual imagery that we could put enough parts and pieces together to get in front of the director and the showrunners, to say, “Is this working? Is this telling the story you want to tell?” And at the same time, working with our production crews in New Zealand to say, “Can we afford to do this? Do we have the time to do this? Do we have the people? Can we get the materials?” And all of that feeding itself back and forth, but it basically was a process, which it mostly is on bigger films that are concept-driven, a process of art, where you sit and you work through a lot of concept art, and you iterate and you iterate, and you figure out what you can and you can’t do. And we ended up with 17,000, more or less, pieces of approved art – that’s not even talking about the iteration of it, and that’s just in the art department, that’s not including props or set deck. If you think about that, even if you average that over two years, we were generating 30 pieces of finished art every day. It was an insane amount of work, but that’s how we got it done was just by literally drawing, thinking, talking, drawing, thinking, talking, drawing, thinking, talking, and doing it step by step of whatever had to be in front of the camera next; work on that.

Which is the set or location that you wish could be on display permanently to sort of show people, “You can’t believe what we did?”

AVERY: [Laughs] There were so many of them that were really great. I mean, Númenor as a whole, that’s four or five acres of scenery, and it’s three or four stories tall. And even that really wasn’t enough to tell the story. We had to figure out how to turn each of those things into other things, as well, in the process of it. But that was a really remarkable bit of set building. It’s a backlot, we build a back lot.

The ship, Elendil’s ship, I just loved that. The craftsmanship on that was amazing, and then the engineering of how we set it up on a gimble and were able to move it, and all that rigging. There was the bottom, 15-20 feet of the sails were real, so all the rigging really works. And we had sailors who could actually make the rigging work. We talked to rigging experts when we were designing the piece, so it was a functional ship on that level. The greens work on this [show]. Simon Lowe, our greensman, was really just a wizard. And how he could get flowers to bloom on the day that they needed to bloom, to make sure that they were there for the camera, I just, still to this day, like, “You are an Elf, man, you’ve got it figured out. Somehow, you knew how to do that.” A lot of those sets were just– they wouldn’t be back.

I mean, my favorite set, in some ways, was actually the dungeon, and that’s because, you know, you read the script and you’re in a medieval fantasy, and you read “interior dungeon,” and you go, “Okay, we all know what a dungeon looks like, right?” That doesn’t feel like Tolkien, you know? That doesn’t feel like Númenor, Númenor is this great place and nobody really gets in trouble in Númenor. So why would you build a deep, dank, dark dungeon for Númenor? So what could it be? And the thing that was always important for everything that we did was, how do you tell all of Tolkien’s backstory? That’s what makes Tolkien; not only is the story compelling, but that whole world that he built, all of that information that underlies everything, how do you get that in the visuals? Because we’re not gonna say all of that. Tolkien doesn’t say all of that. He has a poem or a story, or a little anecdote, that gives you this little window into this big wide world that he’s created. So how do we do that visually?

And the underlying story of Númenor that drives Númenor is their resistance to the idea of dying, right? And the fact that the gods made them die, and gods didn’t make the Elves die, so they’re pissed off at the Elves, but the Elves actually helped them found Númenor. So all of the initial architecture in Númenor is Elvish, and it goes through 2,000 years of development to become not Elvish, or anti-Elvish, it becomes Manish. And how do you make that difference between those two worlds?

So in the dungeon, I thought, “Well, how can we get all of that into one place?” And I said, “Well, why don’t we find a seminary that represents the gods they no longer worship, that has now been turned into this holding cell?” So the idea was, it was a school that was a worshipful religious school that worshiped the gods of the sea because it’s Númenor, so it’s a shrine to Uinen, and what would that look like? Then we did all these murals of seaweed because Uinen means seaweed. We had the sculpture of it. We had all the history on the walls, there’s graffiti from the students in there that wrote it, and so that was all three or 400 years ago. And then 40 years ago, they decided they needed a holding area, and so they built the cell walls inside where the seminarians rooms were, and no, that’s not in the script. That’s not in the specific storytelling, but what it does is that it allows the world to have that depth of what Tolkien adds to his world, and have it visually all be there, and we got to see it, it’s there. I mean, the camera showed it.

I think that, kind of in a nutshell, is what we tried to do in the costumes and the props and the weapons, to try to tell that deep story everywhere we went in the visuals. And that’s the one set that I think we were able to get it to work the clearest and the cleanest, and it was just a beautiful set. That sculpture of Uinen, was just beautiful. It was a beautiful sculpture, and it’s 25 feet tall, it’s amazing.

I know you wouldn’t have taken anything from set because you wouldn’t have done that, but hypothetically, if I were to search your house, what would I find that maybe came from Rings of Power?

AVERY: [Laughs] You know, the funny thing is, I literally did not take anything from the set. I literally did not, for all kinds of reasons. But the thing that I wish I had, more than anything else, is– I mean, when I took this job, it didn’t even cross my mind that I’d have to design the weapons of Middle-earth in the Second Age, that that would be part of what would have to be done, and there’s 2,500 weapons, and another 1,500 arrows. So again, the scope and scale of the thing is ridiculous. And I was able to work with Joe Dunkley, the weapons master at Wētā, and he and his team are all amazing, but I just loved every bit of that weapon design process. And Arondir’s sword, the idea that, as opposed to Noldor, the High Elves are master metalworkers. Elves, as a rule… are master metalworkers.

But the Wood Elves, Sindar, are not. They’re much more into the wood. So how do you make a piece of swordsmanship of weapons that combines this fine metalwork with this fine woodwork? And Joe came up with this idea of how they actually put the metal into the tree and the tree grew over time – because Elves have all the time in the world – and then they would harvest, without killing the tree, they’d harvest that branch that had that metal in it, and then they would silver smith and work the metal and the wood together as one entire unit. And I just think Arondir’s sword is one of the most beautiful things ever. It’s just a beautiful piece of craftsmanship, and it’s a beautiful idea. And again, it’s that deep storytelling of Tolkien’s, where all of that comes from. So if I could have anything, I’d probably want that sword.

I definitely want to touch on your working on the new Captain America. What is it like joining a Marvel property like that, and how much are you looking at all the previous Marvel movies, and then also doing your own thing?

AVERY: I did a Guardians of the Galaxy.

Oh, that’s right! I’m so sorry, I forgot you did Guardians too.

AVERY: So I have a familiarity with the Marvel process. Marvel’s trying some new stuff now. So, we’re telling a Marvel story, but we’re telling it in a different way. So just by that very nature of the story we’re trying to tell, and the way we’re trying to tell it, the intent of this is to be very grounded, to make sure it has that sense of really happening in the world. So it’s a different sense in a lot of ways than particularly some of the more recent pieces have been. And it’s a very deliberate choice, and it’s a fascinating choice and an exciting choice. And it comes with a whole host of different kinds of questions involved in that.

I mean, certainly much in the same way there’s all this backstory for Tolkien, there’s all this back story for the MCU. Not only within the movies themselves now, but there’s also still the parts and pieces that they choose from publishing to feed into all of that. So I have some familiarity with that world. I grew up reading Doctor Strange and Fantastic Four, so that’s something that I have a little relationship with, and Thor. But there’s definitely the sense of being very cognizant of all that and looking for the places that can tie into it. But it’s also very forward-looking at this point. It’s looking to tell a different story that’s been being told, and it’s very cool. It’s really cool. It’s also really nice to be working in a world where I don’t have to light everything with oil lamps and flame, you know? Like, I get to use the light bulb. Yay!

[Laughs] What was your reaction when you read the script? Because I know you must be a Marvel fan. Were you super excited? Was this one of these things where you’re like, “Oh, fans are gonna just dig this?”

AVERY: I was super excited about it because I think the idea behind this, of trying to tell the story in a different way is, it’s really, really interesting. I’ve been talking to this director now for 10 years. We’ve been trying to do projects together for 10 years, and it’s just never worked out, so that’s very exciting to get the opportunity to work with him. And he’s a very clear vision, and I think his vision is very exciting, and what the story wants to do about telling us about very specific interactions with very specific people, I’m very between the idea of this very kind of not normal way of looking at Marvel, and finding the way to make that still feel like Marvel and tell this particular story. It’s very exciting.

You can check out Avery and the crew’s work in Rings of Power Season 1, available on Prime Video.

Source: https://dominioncinemas.net

Category: INTERVIEWS

.jpg)

.jpg)