- ‘Muppets Mayhem’: The Electric Mayhem Spread Wisdom on Their New Album and Its “Melodious Confection” of Tunes

- Michelle Yeoh on Being a Goddess in ‘American Born Chinese’ and Choosing Which Franchise To Be In

- ‘The Wheel of Time’s Ceara Coveney, Dónal Finn & Marcus Rutherford on the Season 2 Premiere

- ‘Transformers: Rise of the Beasts’ Producer on the Costs of CGI and Why He Bought ‘Harry Potter’ for WB

- Finn Wolfhard on ‘Stranger Things’ Season 5, His Directorial Debut, and Joining PlayStation Playmakers

[Editor’s Note: The following containes spoilers for The Equalizer 3.]

you are watching: Antoine Fuqua on ‘Equalizer 3,’ Working with Coolio and Prince, and How Being Shot at 15 Changed His Life

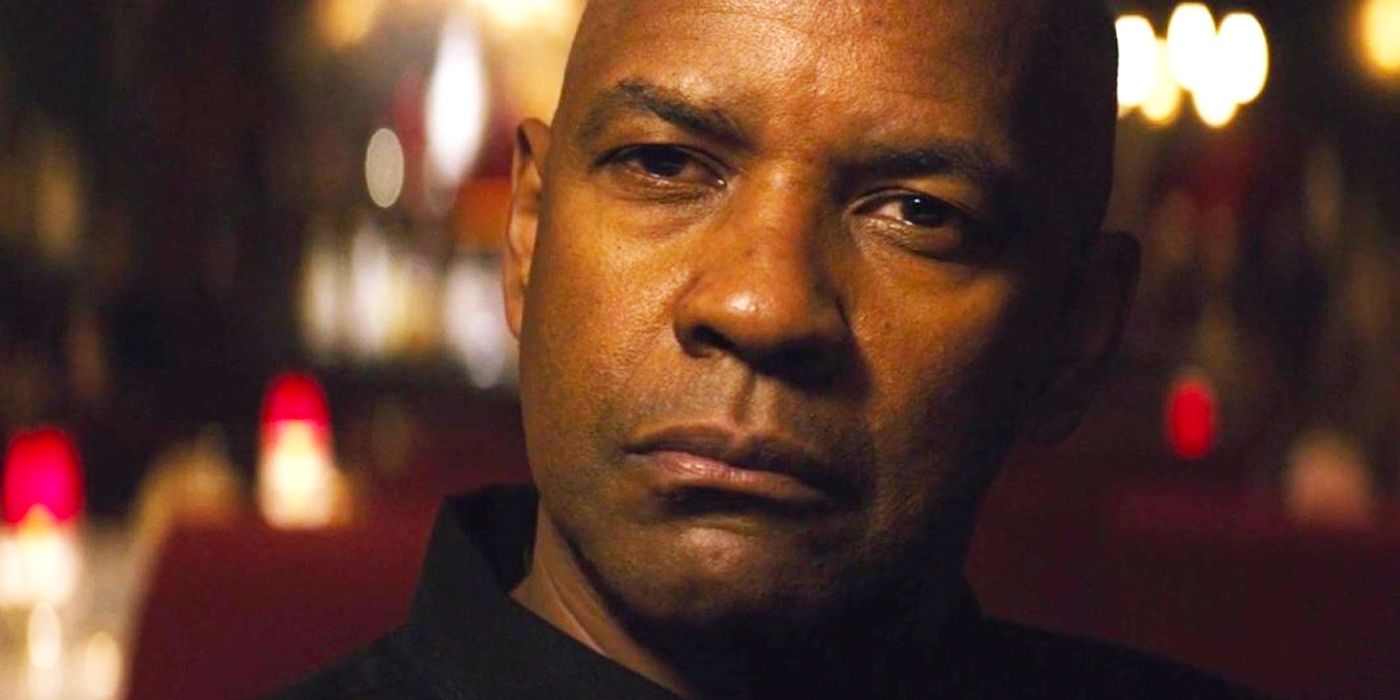

For the third and final entry of the franchise, Collider partnered with Sony and IMAX to offer readers a chance to catch Antoine Fuqua’s The Equalizer 3 on the big screen ahead of its official release. Following the screening, Editor-in-chief Steve Weintraub hosted an exclusive Q&A with the filmmaker to celebrate his past works, look to future projects, and dig into the final journey of Denzel Washington’s action icon, Robert McCall.

In The Equalizer 3, Fuqua and Washington team up again to bring McCall’s heroic arc to its end in a holy trinity of a franchise. The stakes are high and the setting is beautiful on the Amalfi Coast of Italy, where the Equalizer finds himself retiring, or trying to, rather. During their conversation, Fuqua discusses why Italy was so pivotal to McCall’s story, what Akira Kurosawa’s filmography, samurai, and The Equalizer trilogy have in common, and why that ending changed in the edit bay.

Check out the full video above or the transcript below to learn behind-the-scenes morsels on Training Day, the first collaboration between Fuqua and Washington that earned the actor an Academy Award, the film Fuqua almost made—and why he’s glad he didn’t—the life-altering event that set him on the path to becoming a renowned director, his work with Coolio, Prince, and Michelle Pfeiffer, why IMAX is so important, the challenges he and his crew faced filming the Will Smith-led Emancipation, his plans for The Terminal List prequel with Chris Pratt, and tons more.

COLLIDER: First of all, I want to give a huge thank you to IMAX and Sony for partnering up to do the screening, and obviously, a thank you to you for doing this tonight. If someone has never seen anything you’ve directed, what is the first thing you’d like them to watch and why?

ANTOINE FUQUA: Probably Training Day. Training Day was really the film that was the most personal at that time in my life. I was looking for a movie like that. I was writing a story about a cat named Monster Kody, based on a book called Monster, but I couldn’t get that film made. It was about the streets, an LA Crip, he started killing when he was 11 years old. It’s an amazing story. I would have completely fucked it up though if I had got it made because I was focused on the wrong hero. His mother was the hero of the story, right? So back then, I didn’t realize that. But I couldn’t get that movie made, and luckily I didn’t. But when Training Day came, it was another way in, to tell the stories of the streets that I know.

I read that something happened to you when you were 15 years old that changed your life and literally helped you on this path to becoming a filmmaker.

FUQUA: Yeah, wrong place, wrong time. I was shot when I was 15 going to the store to get macaroni and cheese for my mother back in Pittsburgh. It was raining, and a guy got robbed, and he just stepped out with a shotgun. He just started shooting, and me and my buddy, Clifford, just happened to be cutting through an alleyway. And, yeah, luckily there was an A&P supermarket we could run into, and that changed my life, really. Just simply because it makes you realize how fragile life is, how quickly it can go, and if you got dreams and aspirations, you better do it right now because tomorrow is not promised. The next second is not promised.

You know, I was talking back to my grandmother, and she said, “You know, God doesn’t like ugly.” Boy, was she right. [Laughs] And so, yeah, after that, I started going to the movie theaters quite a bit after that just to not be in the streets.

You’ve directed a number of things. Which of your films do you think changed the most in the editing room in ways you didn’t expect?

FUQUA: They all change in ways, right? Movies change from the script form. It’s made one movie, you storyboard a movie, you design a movie, you cast a movie, and each thing you do, it keeps changing and evolving. By the time you film the movie and get it to the editing bay, it’s changed again. Every one of them. Then when you put it in front of an audience, it’s a different movie because the audience comes in from a different perspective, right? So, they all change quite a bit.

Equalizer is a movie that developed a little bit in the editing bay.

The first one or the third one?

FUQUA: This one, actually. This one developed quite a bit because there’s a pacing in the film and there’s character development, and there’s relationships you want to build, and there’s beautiful Italy, you know, on the Amalfi Coast. You can kind of fall in love with these shots and these places and these people, and get lost trying to find the right rhythm, the right pace, the right tone, giving the audience enough of each character so they feel fulfilled. You feel like there’s relationships that developed quite a bit with this one. There’s more; there are a lot of things on the editing room floor that would slow things down, and also it was hurting other areas.

Even the ending that you just witnessed, that ending was from another scene. It kind of comes to me sometime in the middle of the night, I’m like, “But we had a whole different ending.” And I thought, “This is about a celebration of the people, of the place.” That soccer game was earlier, and I called my editor, Conrad Buff, and I said, “What if we put that at the end, so he’s there with the people?” And it was one of those rare moments with Denzel when Denzel is dancing and smiling, and anybody that knows Denzel, Steven, that’s not all the time, you know? So he was dancing and smiling, and I just thought, “That’s a proper way to say goodbye to Robert McCall in a positive way.” So this one developed quite a bit in the editing bay.

I wanna jump backward if you don’t mind. Early in your career, you directed a lot of music videos. Is there one, besides Coolio and “Gangsta’s Paradise,” that really sticks out for you as one you wish more people would watch?

FUQUA: It’s hard. There’s one that sticks out to me because of the whole situation and how it came about and who it was. It was Prince. Prince was a wild one, man. I love Prince. He called me one day to come down to his place, and it was about minus 21 degrees, it was freezing – you could spit and it would freeze. You know, Prince works on his own time, man. So, I’m in the bed sleeping—I think it was two or three in the morning—and Prince had a deep voice to people who really knew him, so he would call me up, and he goes, “Wake up,” and I’m like, “Who is this?” He said, “The Boss.” I said, “Whose boss?” He says, “The Boss.” I said, “Whose boss?” He said, “It’s me. Prince.” And I was like, “Oh, what’s happening, man?” And he goes, “I’m ready.” I was like, “To do what?” He said, “Come down to Paisley Park. I’m ready to film “The Most Beautiful Girl in the World” video.” I said, “I haven’t scouted, man. I haven’t prepped anything.” He goes, “No, just come down.”

Freezing cold, I go down to Paisley Park. There’s females everywhere. I mean, just everywhere. I was like, “You’ve already been casting, man!” Like, “What’s happening?” But the crazy thing is I walked in, there’s these long steps he had, and I was looking for him, and I saw this red outfit coming down with these heels on. I mean, they were see-through paisley, and I’m just like, “What the fuck?” And he comes down, and he stands a few steps ahead of me, and you can see right through it, and he was like, “I’m ready.” I was like, “You gonna wear that?” [Laughs] He goes, “Yeah.” So, I called my DP, Giorgio [Scali]. He had a sound stage and all that, and we just start doing it, man. It was, like, four or five in the morning. We just got going, set him up on the stage. I said, “Shadow all that down here,” because he wasn’t changing his clothes. It was Prince. But yeah, that one just stands out to me because of Prince being so special that night, you know? That one stands out for me.

Thank you for sharing that. What do you think would surprise people to learn about making a big Hollywood movie?

FUQUA: There’s so many things that would surprise people about making a Hollywood movie. One of the things that’s most surprising is how collaboration and working together is the only way you’re gonna make a movie in Hollywood. The only way. You need so many people to do it. I tell PAs and everybody else, “This is your movie too. Your name’s on it forever, as well.” You know what I mean? “So, get it together if that’s what you wanna do.”

Compromising is normally a bad word, and it’s not really in a Hollywood movie because sometimes compromising, in the right way with a positive attitude, could lead to something you never saw coming. I’ve had many arguments with [Sony CEO] Tom Rothman. I love Tom. Me and Tom disagreed on a lot of different things, but somehow, when you get in the mix with them in a positive way, there’s always something that somebody’s feeling, and if you’re smart enough to listen, you never know what that might be. It might be four scenes before or four scenes after. It’s not this scene that’s bothering them, it’s the scene here that’s causing this to be a problem. So you have to constantly be fluid and open to listen, at least.

We all come into a thing thinking that we’re gonna be the next [Martin] Scorsese or the next [Francis Ford] Coppola and all that until you meet them and they tell you all the crazy things they went through for some of the greatest scenes ever made. So, you just have to be open. That’s always surprising to people, that you have to be willing to be open and compromise but not in a negative way. Just be open.

You’ve been directing for over 20 years. When you step on set, how has your process changed from when you first made The Replacement Killers to Equalizer? Is it a similar thing with you or have you changed as a result of all the films you’ve made?

FUQUA: I’ve changed quite a bit. I’m much more patient. It’s like an athlete; the game slows down a bit and you start seeing things differently – what I call rubber balls and glass balls, right? The rubber balls bounce back up, the glass balls break. You gotta know what’s what.

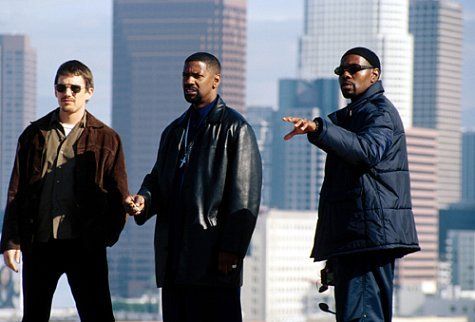

But also, Training Day was a turning point for me, a reminder really, because when I was doing the scenes with Denzel and Ethan [Hawke], I literally would sit on an apple box and once I looked through the lens, I never went to the monitor. I sat literally watching these two master actors go at it, and it was the most fun I ever had. I was laughing my ass off and trying not to interfere with the dialogue. I would forget to yell cut half the time and shit, and Denzel would look back at me and go, “You gonna yell cut?” And I was like, “Oh yeah, cut.” [Laughs] Because it was like, that’s the reason you do it. That’s the reason you do it, to watch these amazing individuals become these people. Coming out of music videos and commercials, it was a visual medium, so everything we do is all about style and being cool, and you realize that’s nice and all that, but nobody gives a fuck if you don’t care about the people in the film, the characters. So that changed me quite a bit. It reminded me why I wanted to make the movies.

I read you are a big [Akira] Kurosawa fan.

FUQUA: Big time, yeah.

For someone who has not seen any of his work, obviously, you should watch his resume, but what’s the one or two that you really want to single out and tell people, “You need to go watch these?”

FUQUA: Well, you should certainly watch Seven Samurai. I never thought I would get a chance to even– I made Magnificent Seven, which is based on the Seven Samurai. The Seven Samurai is the reason I make movies, and when people like you, when we talk, bring it up to me, I realize there’s a throughline about justice. The samurai, who’s helping other people for a bowl of rice, they’re doing it for no other reason but because it’s the right thing to do. That’s what The Equalizer really is, is samurai, right? Which is what samurai means: to serve. And I find myself making the same movie in some way. It’s all about justice. So, that’s one you should certainly watch. Ran, you should definitely watch. I believe Ran was based on King Lear. It’s an amazing film just visually. You’re not gonna do better watching either one of those films.

Yeah, his resume is not bad.

see more : ‘One Piece’ Showrunner on Adapting the Beloved Manga and a Possible Season 2

FUQUA: Not bad, not bad.

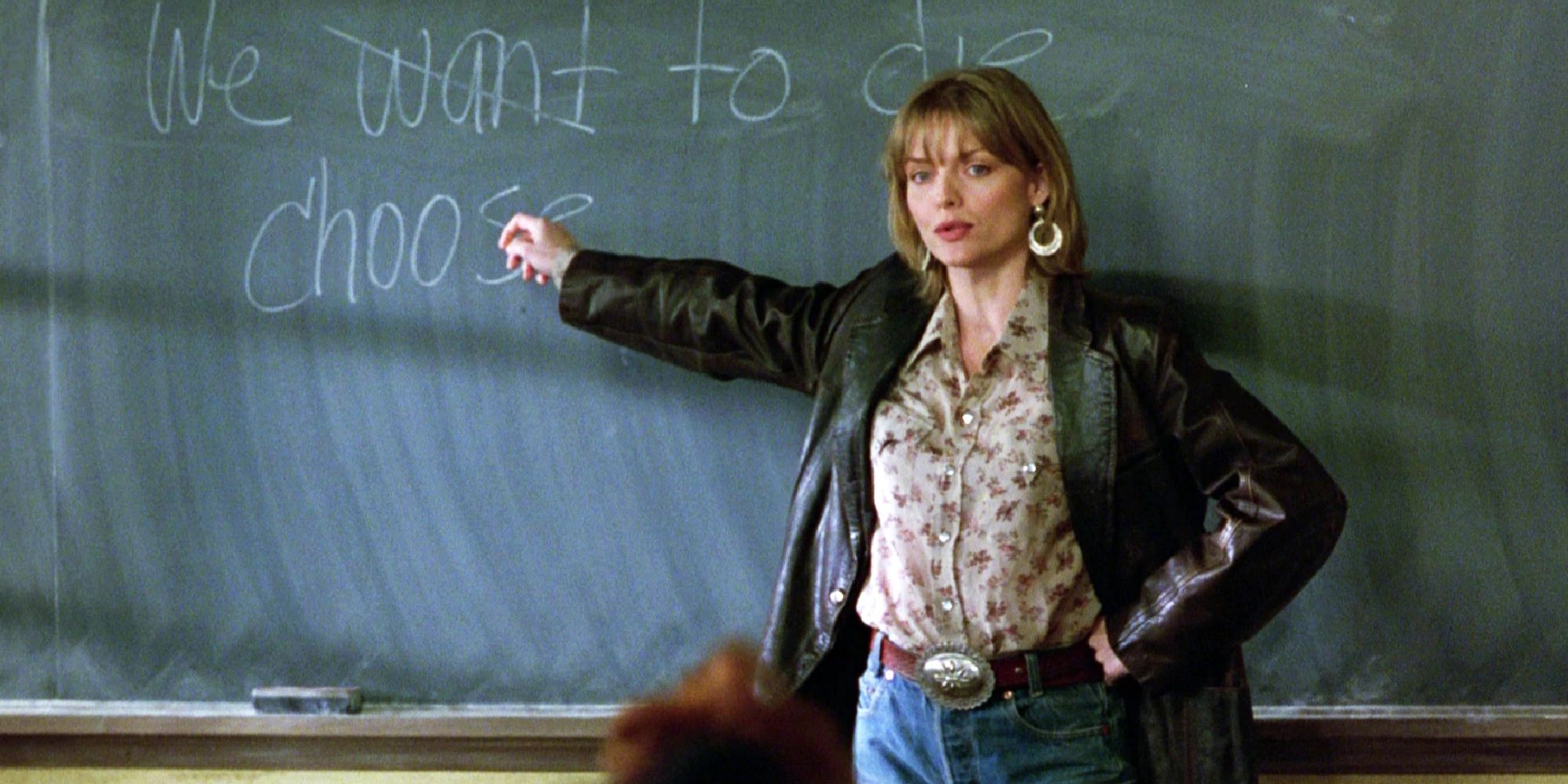

So you did the Coolio video, “Gangsta’s Paradise,” and that video actually opened doors for you to do what you’re doing. Talk a little bit about, before you were a movie director, getting to direct Michelle Pfeiffer and how that video changed your life.

FUQUA: That was interesting. I was, at the time, at Propaganda Films doing commercials and videos, and I got a call from Jerry Bruckheimer to do a music video for Dangerous Minds with Coolio, and I was like, “Yeah, that’d be cool. I’d like to do it, but if Michelle Pfeiffer is in it would be better.” And I’m thinking Jerry’s gonna be like, “Yeah, okay, that’s not gonna happen.” And he goes, “Okay.” We talked, and he called me back, I think a couple of days later, and he goes, “Here’s her number, call her and tell her your idea.” And I was like, “Really?” “Yeah.” So I called her, and I’m nervous, and she’s so cool, man. She was the nicest lady. I told her the idea, and she said, “Alright, let’s do it.”

When I did that video, the movie became a big hit, and everyone thought the images in that film were in the movie, and that’s when Hollywood started combining music videos, at that time, with the films. Monster Kody, the kid I was talking about, his son is actually in that video. I put him in there. So, that changed my life. The agents started calling after that, and you know, the whole Hollywood thing. For a long time, people thought I was this French director – you know, Antoine Fuqua. I’d have people come in the room and look at me and go, “Hey, could you go get me some coffee?” And I was like, “No, I am Antoine Fuqua,” and he was like, “Oh!” So yeah, Hollywood started calling, and John Wu called, and it went from there.

I can’t imagine that phone call.

FUQUA: I couldn’t either.

Of the films you’ve made, which shot or sequence gave you the most nightmares, the toughest to pull off?

FUQUA: Oh, I think everything in Emancipation. Everything in there was so hard to make. That film was shot, it was 100-and-God-knows-what degrees every day in New Orleans. We filmed it in the swamps. You can’t put anything on the ground; everything in there wants to kill you. Alligators everywhere, a hurricane shut us down, COVID shut us down, a tornado shut us down, the subject matter was heartbreaking every day, of course. The battle scene was probably the most complicated thing I’ve ever done in Emancipation.

The first time you directed Denzel, he wins an Oscar. I’m joking around about this, but does that mean you can pretty much just text him any time and be like, “I’m making this movie, so you’re coming, right?”

FUQUA: [Laughs] Yes and no. So, I said, “Denzel, I need to have a coffee with you, man. I want to talk to you about this movie.” And he goes, “Alright.” So we get together, and I had a whole pitch. I said, “So, the sun is coming up. This man on this black horse comes…” He goes, “Wait, what?” I said, “A man on his horse,” and Denzel’s like, “I’m not gonna get on a horse.” [Laughs] I said, “No, no, let me finish! Magnificent Seven…” And he just sat back and listened to me, let me get out my pitch. Like halfway through my pitch, I’m thinking, “Denzel is gonna get up and walk away at any moment. He’s gonna be like, ‘No, I’m not getting on the damn horse playing a cowboy,’” but he listened. He listened for a while. That took a while to get him to say yes to Magnificent Seven.

But he still did.

FUQUA: But he still did, yeah.

Jumping into Equalizer. You’ve now made three films, and the thing about Hollywood is that they always talk about, “Oh, we’ll make a sequel, blah, blah, blah.” It never happens. What is it about this character and these films that resonate with so many people that is the franchise of you and Denzel?

FUQUA: Denzel himself is the draw, obviously. With Sony and the producers, Todd Black and Jason Blumenthal, at one point, we did a test asking people—a random test, I think they did a whole survey—what was most important to most people: money, fame, or justice? What do you think won? Justice. It’s about justice. People want justice, even if it’s in a Hollywood fun way. They want justice, and they want to see Denzel Washington dishing it out. But the bad guys have to be real bad guys. It’s gotta feel like there’s a connection because he’s a working man’s hero. He’s an everyday hero. He’s not flying around in capes and doing flips and all that shit. He’s like a guy who could be anybody in his room. I think people are connecting to that accessibility.

I’ve read that this is the last installment of this franchise. I’m gonna just use one word: why?

FUQUA: I think we’ve explored Robert McCall enough. Everything has to come to an end. It’s a nice send-off that he’s found a place. Because the first one is about finding purpose. He was trying to find a purpose, and he found it. The second one is about dealing with the past—his wife dying, Susan getting murdered, his friends betraying him—and he had to deal with his past. This one is about finding a place in life that you feel could be home and some peace. Where do you go from that? A prequel? John David [Washington]?

I’m curious how you ended up in Italy.

FUQUA: How are you gonna ask somebody how you end up in Italy? [Laughs]

There’s obviously the whole world, so how did you pick Italy besides the amazing food and wine?

FUQUA: Denzel loves Italy. He’s been going to Italy with his children since they were babies. Positano and the Mediterranean. Then he introduced me to it years ago, so I started going there a lot and spending time there on the Amalfi Coast. We talked about different places, but I wanted it to be a place that he felt at home, that he felt comfortable with. Also—I forget which film I was promoting—me and Denzel were together in Rome, and we walked out of this restaurant, and we couldn’t get down the street. There were so many people that found out that he was there. It was just packed, just crazy like The Beatles, and I was like, “Let me get the fuck out of here, man,” because he got bodyguards, I’m by myself. I’m with Denzel and his people, you know? [Laughs] But I realized what an international star he was, and Italy was a place that felt warm to him. And I watch how people respond to him in Italy when we sit and have dinner together, and mama comes out. She’s feeding us, she wouldn’t stop feeding us, you know? And the wine kept flowing, and they’re just loving. And I said, “Let’s set it somewhere that he feels comfortable as well.” So that’s how Italy came out.

Plus, it’s also an amazing place. I mean, to film in Rome and Cinecittà, where [Federico] Fellini filmed, to film in Naples, which is an amazing city. If anybody’s been in Naples, it’s gritty. It reminds me of New York in the ‘70s, and then film on the Amalfi Coast. That place is called Atrani, and to wake up every day looking at the Mediterranean, it’s like, where else are you gonna film it? Budapest? You know what I’m saying?

This film is going to be like The White Lotus in terms of getting people to Italy, you know?

FUQUA: Yeah, maybe, maybe. It’s a beautiful place. I suggest you go if you haven’t been.

So, this movie is a little violent. There’s a little blood and guts. Where do you find the line of what you’re willing to show and do you ever get studio pushback or the MPAA pushback?

FUQUA: I’ve got no pushback from the studio or the MPAA. The violence, for me as a director, it’s like dialogue. The violence is dialogue for me. You have someone like Denzel Washington, it can’t just be violence, there has to be a reason it’s happening, and you have to still see him performing. That’s the thing I focus on a lot.

The first one, when he puts the corkscrew in the guy, is because these guys were human trafficking little girls. Me and Denzel, I said, “I want you to see the light go out in this motherfucker’s eyes,” you know? That’s how evil this person is. And so the audience responds to that, and anybody who watches the movie feels the same, so you can get away with that because the bad guys were so bad. That’s one of the things that helps get past the core because he becomes the monster, right?

This movie, in particular, Equalizer 3, is about they’re terrorizing people, right? They’re terrorists. That’s what they are. And so, what happens when you flip that? What happens when you come home and all your people are dead and your boy’s hanging with a corkscrew in his mouth, just the way you threw the old man out the window, right? So now you’re the victim, now you’re being terrorized. So when you do that for the story– And also, mentally, where is Robert McCall? The violence is all about where he is mentally. So, in the beginning, he’s darker, he’s mean, he shoots the guy in the ass. He tortures him because he’s dealing with his own internal struggle with violence. That’s one of the things me and Denzel talked a lot about was, there’s guys that get off on violence. It just happens, right? There’s special forces people who live a certain life, and it becomes a thing, right? It’s like sex. Robert McCall was on the edge. He’s alone now. He has no one else. So, is he killing for himself now, or is he really doing it for the people?

So, of course, God steps in—we all saw the movie now—and says, “You need to slow down and rethink what you’re doing and what you’re doing it for.” So, that violence was about where he was mentally. That’s why he puts the gun to his head because he doesn’t even like himself anymore. So the violence is all about character, especially with someone like Denzel Washington. Like I said, he’s not doing the ballet. He’s performing.

Obviously, we’re in IMAX headquarters, and we’re watching it in IMAX. It’s my favorite format. I love IMAX. Talk a little bit about why you should see films in IMAX, especially Equalizer.

FUQUA: The scope, you’re never gonna see it like this ever again. The scope of this is just incredible. The sound. It’s what you make movies for, to put it on a screen like this, to have this sort of shared experience in IMAX. You’ll never see it again like this, you know? It’s really important to experience it this way. This is what cinema is. This is what it’s all about. When I was a little boy and I first saw Close Encounters [of the Third Kind], those films with my dad, they were larger than life. That’s what movies are about. IMAX is the best way to watch it.

Everyone says it, but there really is nothing like seeing a movie in a movie theater.

FUQUA: It’s a shared experience.That’s what we make it for. Like I said, movies are remade. You make a movie. I sit there by myself in the screening rooms and stuff with my popcorn and Coke, and yeah, it’s great. Then I get in a room with, like, three or four other people and it changes; get in a room with more people, they laugh at certain places, and I’m like, “Was that supposed to be funny? Was that supposed to be a serious scene?” But you start to experience it in a whole different way, and that’s the magic of it.

What have you learned, in this film in particular, from any friends and family screenings or test screenings that impacted the finished film?

FUQUA: What people care about, sometimes, are the smallest things. I’ll give you an example from the first one. The girl gets robbed at the cash register, and there’s a whole scene where McCall goes and handles the guy that robbed the place with the hammer. I remember saying, “I’m just gonna see him pick up the hammer. We already know what McCall does.” And at the end of the movie, the ring is in the drawer, right? The drawer opens, and her ring is there. I fucking hated that scene. The studio was like, “Oh no, it’s beautiful,” and I was like, “It’s so corny. I don’t wanna put that in the movie.” The audience loved it. They love the sentiment of it. They loved it. Sometimes we get so caught up on how fucking cool we are and what we think we know. Until you get in a room with a bunch of people, you don’t know shit. You don’t know anything because you make it for the audience. When we did the cards, that was one of their favorite moments. So, that’s a big lesson.

I’m curious what it’s like in the editing room. How much does Denzel visit you in the editing room?

FUQUA: Never. He’s never visited me in the editing room. Denzel doesn’t come look at my monitor. That’s part of our relationship. On Training Day, we did that scene in the cafe when he tells Ethan Hawke to pay the bill. I got what I wanted—you know, Denzel Washington—and I was like, “Dude, you want to come over and look at the monitor?” He said, “You’re flying this plane, man. Call me when you need me,” and got up and walked away. I’m like, “Oh shit, I better not fuck this up.” But that sort of trust, you know, it freed me, right? We had an agreement that we never tie each other’s hands, and that was our agreement, and that’s our trust. So he never ever has come in the editing bay. He doesn’t come into my monitors, he doesn’t come and look at what I’m doing. He gives you his performance, the choices, we discuss those things, and he goes off and chills until we need him. That’s our relationship.

How many takes do you typically like to do when you’re filming, and how many takes does Denzel like to do?

FUQUA: We only do what we really need. Three takes is a lot for me and Denzel. Like, three to four takes. There’s always some technical thing here or there. We both believe—and every actor’s different—you only get that moment once. That’s what makes great actors great actors. You get that moment once. No matter what they’re doing, it’s never gonna be the same. The more takes you do down the line, you start to burn out the rawness of it, the truth. The truth normally comes early; it comes right away. If you’re a great actor, you did your work before, and that’s what Denzel does. So, maybe three takes. If it’s a fourth take, we’re going off book a little bit, and we’re playing because we’re having some fun and we wanna fuck around a little bit, or he’s got something he wants to do, or I’ll go to him and say something.

Normally, with Denzel, and I’m blessed, really, because we have this relationship where, I swear, I’ll be sitting there with Denzel, and I’ll go, “Cut.” I’ll go, “D., you know what…?” And he goes, “I already know. I know.” I’m like, “You sure you know?” And then he would do it, and I’m like, “Fuck, that’s weird.” Or I would go to him and say, “I want you to adjust something,” and he would kind of go like, “What did I do? What do you mean?” And I said, “You know, when you did the thing,” and he goes, “I don’t even remember, man. Alright, hold on a second…” because he’s in the moment. That moment is real.

I remember one time he was doing something in Equalizer 2 with the kid in the house, and he was about to do something, and I’m watching him, I’m watching him. He’s used to me watching him for a while, but then, for whatever reason I said, “Okay, cut,” and he went, “Ah!” And I hate to see him that way because it hit me, and I was like, “Oh shit, he was about to do something.” That was gone forever. I didn’t even know what it was he was gonna do. It was something he was about to do, and I fucked that up. You only get that moment once. So, three takes, maybe four if we’re playing a little bit.

You used Robert Richardson as your DP on this and you worked with him on Emancipation. What is he like as a collaborator and what made you want to work with him again on Equalizer 3?

FUQUA: Bob Richardson is just a genius. You know, he has three Academy Awards, and he worked with the greatest directors, my heroes as well—Oliver Stone, Martin Scorsese, and Quentin [Tarantino]. He’s like a little wizard, man, with that gray hair. [Laughs] He’s just magic, and he doesn’t sleep, he’s a lot like me. He’s up all night sending me images and long texts, and sometimes I don’t know what the fuck he’s talking about, but he’s brilliant. He’s a brother, man. I love him, and we’re so similar.

On Emancipation, there’s alligators in that fucking swamp. When I first asked Bob to do the movie, he goes, “Fuck no, I hate snakes. I’m not doing it.” I talked him into doing it, but he was in the swamp with me, man, knee-deep, going out to these places. He was like a warrior, man. And Bob is on the set before everybody. I kept trying to beat him to the set, and I was like, “I’m gonna beat him today. I’m gonna beat him,” and he would be up all night. I’m like, “When the fuck do you sleep?” And he would be on the set before me every time. I’ve never beaten Bob Richardson to the set. But he’s just one of these people that loves cinema. He loves it. He’s an artist and he’s a filmmaker. We discuss script, character, we spend a lot of time together. Genius.

So, Roger Deakins famously shoots with one camera, and Ridley Scott will do six or eight cameras. Completely, radically different ways of working. Which way do you like to work and has it changed in your career?

FUQUA: In the beginning I liked a lot of cameras, coming out of commercials and videos. You wanna capture everything, you’re shooting every fucking angle. As I mature, one camera is really the focus, but every once in a while I’ll have maybe two, depends on the scene. But it needs to be very specific to what I want. It’s not a hosing down thing. One camera is what it’s really all about for me now. The relationship between me and that frame has to be complete. I can’t think about the other cameras anymore. When you’re younger, you are not confident enough. I wasn’t when I was younger. I didn’t want to miss anything, but now, I’m pretty precise.

How much do you let go, and are you willing to let your second unit director take on stuff, and how much are you like, “Fuck, I’m shooting that?”

FUQUA: I’m always like, “Fuck, I’m shooting that,” but I met [Robert] Legato, who shot for Scorsese, as well, through Bob, and Rob I have complete trust in. We discuss everything. I storyboard everything, lay it out, and then I always give an artist that room. We get what we want, but then he’ll see something, and like, shit go get it, you know? In Emancipation, there are some great shots in there with the horses chasing – their Rob’s shot. You know, I told him what I wanted, and he would go over there and shoot it, but they bring it to me right away, immediately, and I see it right away. But yeah, if you got a great artist, you gotta let them fly a little bit. By the way, he’s got three Academy Awards, too, I believe. I don’t have one, so I think Rob can shoot a couple of things for me. [Laughs]

The film is like an hour and 45 minutes or so. How long was the cut that you had? Was there a longer cut of the film that you were super happy with?

FUQUA: This film was never more than, I’d say, 2:15, and I wasn’t happy with it. I couldn’t find a rhythm of it at first, for whatever reason. I think a lot of it [was] because, coming out of Emancipation, the whole thing—I’m not gonna get into that—but the whole Academy thing, it took a toll on me a little bit that I didn’t realize. I had to catch up to myself a little bit. So, my rhythm was off, and so when I got into the editing bay, my rhythm felt off, and it took me a while. I had to watch it and watch it, and let it come to me more and more and more to where it felt right, the heartbeat felt right. Then, as I chiseled and chiseled and chiseled and chiseled away, I was still like, “Oh, this is getting better,” and I chiseled some more. I was like, “I’m still not missing it,” and I cut this out, and I was like, “I didn’t miss that at all!” And I kept going until I felt like, “Okay, if I go any further, I’m gonna hurt it.”

Then I called Conrad, like, literally in the mix the day before we finished, and I was telling him, “Let’s put this thing back, let’s put that back,” and he’s like, “What the fuck are you talking about? The movie’s done.” I was like, “I gotta put it back. I gotta find a way to do it.” Then I started putting a couple of things back in because my rhythm was just off, and things were coming a little late to me.

What are you like directing on set? Not with Denzel because, obviously, you have a shorthand, but with other people, how do you like to direct, and what do you do when you’re not getting what you want?

FUQUA: [Laughs] When I was younger, I would yell, which is stupid. I was mean, I think, because some of it comes out of fear of failure. You react like a fucking child, and that doesn’t get you what you want. Now, you know, like I said, I’m much more patient. I plan differently now. If I’m not getting what I want– I’ll always get what I want. I’m gonna get what I want. But sometimes, like I said, the compromise is, “Okay, I can’t get exactly what I want, but I’m gonna create something out of this moment.” Weather, not enough money, anything can happen, all kind of weird shit. Now my strategy is, “Okay, what’s the gift? If I have done everything I can do to get everything I can get out of this, but I can’t get what I want, what’s the gift?” You know what I’m saying? There’s a gift in there somewhere, right? That’s how I see it. Because if I’ve exhausted everything, what’s the gift? Sometimes that’s like, “You know what? Fuck, this is actually better.” Sometimes. There’s some days where I can’t even– I don’t even watch my own films back because I remember those moments where I didn’t get a fucking gift, and I’m like, “Shit, I wish I could have done that a little better.” [Laughs] But my directing is much more patient.

You are possibly making a Michael Jackson film.

FUQUA: Yeah, I’m very excited about that. Absolutely. I can’t get into it right now, obviously, but man, I’m telling you, I’m very excited about that movie. I’m very excited about telling Michael’s story.

So you were involved in The Terminal List.

FUQUA: I produced it.

It was super successful on Prime Video, and Chris Pratt is also super popular on Prime Video. What do you think it is about that series, that material, that resonated and caused it to be such a huge hit?

FUQUA: Oh man, it’s fun. Chris is a badass in it, for real, playing a Navy Seal. Again, it’s justice. His family gets murdered, and the people who murdered his family are going to meet the dark wolf, and that’s what it is. It’s justice. People want to see justice. That’s what it’s all about.

They’re making a prequel series.

FUQUA: Yes, we are doing it.

How is that moving along?

FUQUA: Well, the strike stopped everything, obviously, but we’re moving along. We were at a good click. We’re excited about it. Chris and the team, we’re ready to go. As soon as they solve the issues, we’re off and running.

The Equalizer 3 is in theaters now.

Source: https://dominioncinemas.net

Category: INTERVIEWS